Israeli–Palestinian conflict

| Israeli–Palestinian conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab–Israeli conflict | |||||||||

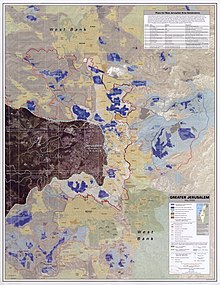

Situation in the Israeli-occupied territories, as of December 2011[update], per the United Nations OCHA.[2] See here for a more detailed and updated map. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

1948–present: |

1948–present:

1949–1956: 1964–2005: 2007–present:

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 9,901–9,922 killed | 84,638–90,824 killed | ||||||||

|

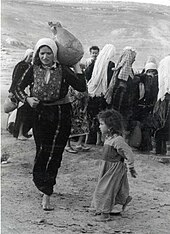

More than 700,000 Palestinians displaced[3] with a further 413,000 Palestinians displaced in the Six-Day War;[4] 2,000+ Jews displaced in 1948[5] | |||||||||

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is an ongoing military and political conflict about land and self-determination within the territory of the former Mandatory Palestine.[25][26][27] Key aspects of the conflict include the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, the status of Jerusalem, Israeli settlements, borders, security, water rights,[28] the permit regime, Palestinian freedom of movement,[29] and the Palestinian right of return.

The conflict has its origins in the rise of Zionism in the late 19th century in Europe, a movement which aimed to establish a Jewish state through the colonization of Palestine,[30][page needed][31] and the consequent first arrival of Jewish settlers to Ottoman Palestine in 1882.[32] The local Arab population increasingly began to oppose Zionism, primarily out of the fear of territorial displacement and dispossession.[32] The Zionist movement garnered the support of an imperial power in the 1917 Balfour Declaration issued by Britain, which promised to support the creation of a "Jewish homeland" in Palestine. Following British occupation of the formerly Ottoman region during World War I, Mandatory Palestine was established as a British mandate. Increasing Jewish immigration led to tensions between Jews and Arabs which grew into intercommunal conflict.[33][34] In 1936, an Arab revolt erupted demanding independence and an end to British support for Zionism, which was suppressed by the British.[35][36] Eventually tensions led to the UN adopting a partition plan in 1947, triggering a civil war.

During the ensuing 1948 Palestine war, more than half of the mandate's predominantly Palestinian Arab population fled or were expelled by Israeli forces. By the end of the war, Israel was established on most of the former mandate's territory, and the Gaza Strip and the West Bank were controlled by Egypt and Jordan respectively.[37][38] Since the 1967 Six Day War, Israel has been occupying the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, known collectively as the Palestinian territories. Two Palestinian uprisings against Israel and its occupation erupted in 1987 and 2000, the first and second intifadas respectively. Israel's occupation, which is now considered to be the longest military occupation in modern history, has seen it constructing illegal settlements there, creating a system of institutionalized discrimination against Palestinians under its occupation called Israeli apartheid. This discrimination includes Israel's denial of Palestinian refugees from their right of return and right to their lost properties. Israel has also drawn international condemnation for violating the human rights of the Palestinians.[39]

The international community, with the exception of the US and Israel, has been in consensus since the 1980s regarding a settlement of the conflict on the basis of a two-state solution along the 1967 borders and a just resolution for Palestinian refugees. The US and Israel have instead preferred bilateral negotiations rather than a resolution of the conflict on the basis of international law. In recent years, public support for a two-state solution has decreased, with Israeli policy reflecting an interest in maintaining the occupation rather than seeking a permanent resolution to the conflict. In 2007, Israel tightened its blockade of the Gaza Strip and made official its policy of isolating it from the West Bank. Since then, Israel has framed its relationship with Gaza in terms of the laws of war rather than in terms of its status as an occupying power. In a July 2024 ruling, the International Court of Justice rebuffed Israel's stance, determining that the Palestinian territories constitute one political unit and that Israel continues to illegally occupy the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The ICJ also determined that Israeli policies violate the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. Since 2006, Hamas and Israel have fought several wars. Attacks by Hamas-led armed groups in October 2023 in Israel were followed by another war.[40] Israel's actions in Gaza since the start of the 2023 war have been described by international law experts, genocide scholars and human rights organizations as genocidal.[41]

History

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the development of political Zionism and the arrival of Zionist settlers to Palestine.[32][43] During the early 20th century, Arab nationalism also grew within the Ottoman Empire. To gain support from the Arab nationalists, Great Britain initially promised support for the formation of an independent Arab state in Palestine in the McMahon–Hussein correspondence,[44] and with local support it was able to take control of the region in 1917. It later transpired that the British and French governments had secretly made the Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916 not to allow the formation of an independent Arab state.[45]

While Jewish colonization began during this period, it was not until the arrival of more ideologically Zionist immigrants in the decade preceding the First World War that the landscape of Ottoman Palestine would start to significantly change.[46] Land purchases, the eviction of tenant Arab peasants and armed confrontation with Jewish para-military units would all contribute to the Palestinian population's growing fear of territorial displacement and dispossession.[38] From early on, the leadership of the Zionist movement had the idea of "transferring" (a euphemism for ethnic cleansing) the Arab Palestinian population out of the land for the purpose of establishing a Jewish demographic majority.[47][48][49][50][51] According to the Israeli historian Benny Morris the idea of transfer was "inevitable and inbuilt into Zionism".[52] The Arab population felt this threat as early as the 1880s with the arrival of the first aliyah.[38] Chaim Weizmann's efforts to build British support for the Zionist movement would eventually secure the Balfour Declaration, a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine.[53]

1920s

With the creation of the British Mandate in Palestine after the end of the first world war, large-scale Jewish immigration began accompanied by the development of a separate Jewish-controlled sector of the economy supported by foreign capital.[54] The more ardent Zionist ideologues of the Second Aliyah would become the leaders of the Yishuv starting in the 1920s and believed in the separation of Jewish and Arab societies.[32]

Amin al-Husseini, appointed as Grand Mufti of Jerusalem by the British High Commissioner Herbert Samuel, immediately marked Jewish national movement and Jewish immigration to Palestine as the sole enemy to his cause,[55] initiating large-scale riots against the Jews as early as 1920 in Jerusalem and in 1921 in Jaffa. Among the results of the violence was the establishment of the Jewish paramilitary force Haganah. In 1929, a series of violent riots resulted in the deaths of 133 Jews and 116 Arabs, with significant Jewish casualties in Hebron and Safed, and the evacuation of Jews from Hebron and Gaza.[56]

1936–1939 Arab revolt

In the early 1930s, the Arab national struggle in Palestine had drawn many Arab nationalist militants from across the Middle East, such as Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam from Syria, who established the Black Hand militant group and had prepared the grounds for the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. Following the death of al-Qassam at the hands of the British in late 1935, tensions erupted in 1936 into the Arab general strike and general boycott. The strike soon deteriorated into violence, and the Arab revolt was bloodily repressed by the British assisted by the British armed forces of the Jewish Settlement Police, the Jewish Supernumerary Police, and Special Night Squads.[57] The suppression of the revolt would leave at least 10% of the adult male population killed, wounded, imprisoned or exiled.[58] Between the expulsion of much of the Arab leadership and the weakening of the economy, the Palestinians would struggle to confront the growing Zionist movement.[59]

The cost and risks associated with the revolt and the ongoing inter-communal conflict led to a shift in British policies in the region and the appointment of the Peel Commission which recommended creation of a small Jewish country, which the two main Zionist leaders, Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion, accepted on the basis that it would allow for later expansion.[60][61][62] The subsequent White Paper of 1939, which rejected a Jewish state and sought to limit Jewish immigration to the region, was the breaking point in relations between British authorities and the Zionist movement.[63]

1940-1947

The renewed violence, which continued sporadically until the beginning of World War II, ended with around 5,000 causualties on the Arab side and 700 combined on the British and Jewish side total.[64][65][66] With the eruption of World War II, the situation in Mandatory Palestine calmed down. It allowed a shift towards a more moderate stance among Palestinian Arabs under the leadership of the Nashashibi clan and even the establishment of the Jewish–Arab Palestine Regiment under British command, fighting Germans in North Africa. The more radical exiled faction of al-Husseini, however, tended to cooperate with Nazi Germany, and participated in the establishment of a pro-Nazi propaganda machine throughout the Arab world. The defeat of Arab nationalists in Iraq and subsequent relocation of al-Husseini to Nazi-occupied Europe tied his hands regarding field operations in Palestine, though he regularly demanded that the Italians and the Germans bomb Tel Aviv.[56]

During the war, thousands of Palestinian Arabs and Jews fought for the British.[67] Notably, a Jewish–Arab Palestine Regiment, which included thousands of Jews and Palestinian Arabs, was established under British command to fight Nazi Germany in North Africa. The Jewish Agency for Palestine and Palestinian National Defense Party called on Palestine's Jewish and Arab youth to volunteer for the British Army. 30,000 Palestinian Jews and 12,000 Palestinian Arabs enlisted in the British armed forces during the war, while a Jewish Brigade was created in 1944.[68]

By the end of World War II, a crisis over the fate of Holocaust survivors from Europe led to renewed tensions between the Yishuv and Mandate authorities. In the 1944, Jewish groups began to conduct military-style operations against the British, with the aim of persuading Great Britain to accept the formation of a Jewish state. This culminated in the Jewish insurgency in Mandatory Palestine. This sustained Zionist paramilitary campaign of resistance against British authorities, along with the increased illegal immigration of Jewish refugees and 1947 United Nations partition, led to eventual withdrawal of the British from Palestine.[69]

1947 United Nations partition plan

On 29 November 1947, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted Resolution 181(II)[70] recommending the adoption and implementation of a plan to partition Palestine into an Arab state, a Jewish state and the City of Jerusalem.[71] Palestinian Arabs were opposed to the partition.[72] Zionists accepted the partition but planned to expand Israel's borders beyond what was allocated to it by the UN.[73] On the next day, Palestine was swept by violence. For four months, under continuous Arab provocation and attack, the Yishuv was usually on the defensive while occasionally retaliating.[74] The Arab League supported the Arab struggle by forming the volunteer-based Arab Liberation Army, supporting the Palestinian Arab Army of the Holy War, under the leadership of Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni and Hasan Salama. On the Jewish side, the civil war was managed by the major underground militias – the Haganah, Irgun and Lehi – strengthened by numerous Jewish veterans of World War II and foreign volunteers. By spring 1948, it was already clear that the Arab forces were nearing a total collapse, while Yishuv forces gained more and more territory, creating a large scale refugee problem of Palestinian Arabs.[56]

1948 Arab–Israeli War

Following the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel on 14 May 1948, the Arab League decided to intervene on behalf of Palestinian Arabs, marching their forces into former British Palestine, beginning the main phase of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[71] The overall fighting, leading to around 15,000 casualties, resulted in cease-fire and armistice agreements of 1949, with Israel holding much of the former Mandate territory, Jordan occupying and later annexing the West Bank and Egypt taking over the Gaza Strip, where the All-Palestine Government was declared by the Arab League on 22 September 1948.[57] The 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine and 1948 Arab-Israeli War resulted in the ethnic cleansing of 750,000 Palestinian Arabs.[37]

1949 Conflict about rigth to return to Israel

1949 started a conflict between Israel and the Palestinians about who has the right to return to Israel after the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Who has the right to return is still a conflict between Israel and the Palestinians. In 1949, the UN passed a resolution that aimed to allow most refugees to return. But Israel refused to implement it. The State of Israel passed in 1950 the Law of Return. The main rule of this law is that all Jews who want to settle in Israel have the right to become citizens of Israel only a short time after they arrive to settle in the country. The rule has also been applied to Jews who have never previously lived in Israel.[75] For the majority of non-Jewish refugees from Israel, the law has meant that they have been refused the right to return and become Israeli citizens. They became stateless, people who lack citizenship in any country that is generally recognized as a country.

1956 Suez Crisis

Through the 1950s, Jordan and Egypt supported the Palestinian Fedayeen militants' cross-border attacks into Israel, while Israel carried out its own reprisal operations in the host countries. The 1956 Suez Crisis resulted in a short-term Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip and exile of the All-Palestine Government, which was later restored with Israeli withdrawal. The All-Palestine Government was completely abandoned by Egypt in 1959 and was officially merged into the United Arab Republic, to the detriment of the Palestinian national movement. Gaza Strip then was put under the authority of the Egyptian military administrator, making it a de facto military occupation. In 1964, however, a new organization, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), was established by Yasser Arafat.[71] It immediately won the support of most Arab League governments and was granted a seat in the Arab League.

1967 Six-Day War

In the 1967 Arab-Israel War, Israel occupied the Palestinian West Bank, East Jerusalem, Gaza Strip, Egyptian Sinai, Syrian Golan Heights, and two islands in the Gulf of Aqaba.

The war exerted a significant effect upon Palestinian nationalism, as the PLO was unable to establish any control on the ground and ultimately established its headquarters in Jordan, from where it supported the Jordanian army during the War of Attrition. However, the Palestinian base in Jordan collapsed with the Jordanian–Palestinian civil war in 1970, after which the PLO was forced to relocate to South Lebanon.

In the mid-1970s, the international community converged on a framework to resolve the conflict through the establishment of an independent Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza. This "land for peace" proposal was endorsed by the ICJ and UN.[76]

1973 Yom Kippur War

On 6 October 1973, a coalition of Arab forces consisting of mainly Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack against Israel on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur. Despite this, the war concluded with an Israeli victory, with both sides suffering tremendous casualties.

Following the end of the war, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 338 confirming the land-for-peace principle established in Resolution 242, initiating the Middle East peace process. The Arab defeat would play an important role in the PLO's willingness to pursue a negotiated settlement to the conflict,[77][78] while many Israelis began to believe that the area under Israeli occupation could not be held indefinitely by force.[79][80]

The Camp David Accords, agreed upon by Israel and Egypt in 1978, primarily aimed to establish a peace treaty between the two countries. The accords also proposed the creation of a "Self-Governing Authority" for the Arab population in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, excluding Jerusalem, under Israeli control. A peace treaty based on these accords was signed in 1979, leading to Israel's withdrawal from the occupied Egyptian Sinai Peninsula by 1982.[81][82]

1982 Lebanon War

Palestinian insurgency in South Lebanon peaked in the early 1970s, as Lebanon was used as a base to launch attacks on northern Israel and airplane hijacking campaigns worldwide, which drew Israeli retaliation. During the Lebanese Civil War, Palestinian militants continued to launch attacks against Israel while also battling opponents within Lebanon. In 1978, the Coastal Road massacre led to the Israeli full-scale invasion known as Operation Litani. This operation sought to dislodge the PLO from Lebanon while expanding the area under the control of the Israeli allied Christian militias in southern Lebanon. The operation succeeded in leaving a large portion of the south in control of the Israeli proxy which would eventually form the South Lebanon Army. Under United States pressure, Israeli forces would eventually withdraw from Lebanon.[83][84][85][86]

In 1982, Israel, having secured its southern border with Egypt, sought to resolve the Palestinian issue by attempting to dismantle the military and political power of the PLO in Lebanon.[87] The goal was to establish a friendly regime in Lebanon and continue its policy of settlement and annexation in occupied Palestine.[88][89][90] The PLO had observed the latest ceasefire with Israel and shown a preference for negotiations over military operations. As a result, Israel sought to remove the PLO as a potential negotiating partner.[91][92][93] Most Palestinian militants were defeated within several weeks, Beirut was captured, and the PLO headquarters were evacuated to Tunisia in June by Yasser Arafat's decision.[57]

First Intifada (1987–1993)

The first Palestinian uprising began in 1987 as a response to Israel's military occupation, escalating attacks on Palestinians, and policies of settlement building and collective punishment. The uprising largely consisted of nonviolent acts of civil disobedience and protest, and was largely led by grassroots popular, youth, and women's committees.[94][95] By the early 1990s, the conflict, termed the First Intifada, was the focus of international settlement efforts, in part motivated by the success of the Egyptian–Israeli peace treaty of 1982. Eventually the Israeli–Palestinian peace process led to the Oslo Accords of 1993, allowing the PLO to relocate from Tunisia and take ground in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, establishing the Palestinian National Authority. The peace process also had significant opposition among elements of Palestinian society, such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, who immediately initiated a campaign of attacks targeting Israelis. Following hundreds of casualties and a wave of anti-government propaganda, Israeli Prime Minister Rabin was assassinated by an Israeli far-right extremist who objected to the peace initiative. This struck a serious blow to the peace process, which in 1996 led to the newly elected government of Israel backing off from the process, to some degree.[56]

Second Intifada (2000–2005)

Following several years of unsuccessful negotiations, the conflict re-erupted as the Second Intifada in September 2000.[57] The violence, escalating into an open conflict between the Palestinian National Security Forces and the Israel Defense Forces, lasted until 2004/2005 and led to thousands of fatalities. In 2005, Israeli Prime Minister Sharon ordered the removal of Israeli settlers and soldiers from Gaza. Israel and its Supreme Court formally declared an end to occupation, saying it "had no effective control over what occurred" in Gaza.[96] However, the United Nations, Human Rights Watch and many other international bodies and NGOs continue to consider Israel to be the occupying power of the Gaza Strip as Israel controls Gaza Strip's airspace, territorial waters and controls the movement of people or goods in or out of Gaza by air or sea.[96][97][98]

Fatah–Hamas split (2006–2007)

In 2006, Hamas won a plurality of 44% in the Palestinian parliamentary election. Israel responded it would begin economic sanctions unless Hamas agreed to accept prior Israeli–Palestinian agreements, forswear violence, and recognize Israel's right to exist, all of which Hamas rejected.[99] After internal Palestinian political struggle between Fatah and Hamas erupted into the Battle of Gaza (2007), Hamas took full control of the area.[100] In 2007, Israel imposed a naval blockade on the Gaza Strip, and cooperation with Egypt allowed a ground blockade of the Egyptian border.

The tensions between Israel and Hamas escalated until late 2008, when Israel launched operation Cast Lead upon Gaza, resulting in thousands of civilian casualties and billions of dollars in damage. By February 2009, a ceasefire was signed with international mediation between the parties, though the occupation and small and sporadic eruptions of violence continued.[citation needed]

In 2011, a Palestinian Authority attempt to gain UN membership as a fully sovereign state failed. In Hamas-controlled Gaza, sporadic rocket attacks on Israel and Israeli air raids continued to occur.[101][102][103][104] In November 2012, Palestinian representation in the UN was upgraded to a non-member observer state, and its mission title was changed from "Palestine (represented by PLO)" to "State of Palestine". In 2014, another war broke out between Israel and Gaza, resulting in over 70 Israeli and over 2,000 Palestinian casualties.[105]

Israel–Hamas war (2023–present)

After the 2014 war and 2021 crisis, Hamas began planning an attack on Israel.[106] In 2022, Netanyahu returned to power while headlining a hardline far-right government,[107] which led to greater political strife in Israel[108] and clashes in the Palestinian territories.[109] This culminated in the 2023 Israel–Hamas war, when Hamas-led militant groups launched a surprise attack on southern Israel from the Gaza Strip, killing more than 1,200 Israeli civilians and military personnel and taking hostages.[110][111] The Israeli military retaliated by conducting an extensive aerial bombardment campaign on Gaza,[112] followed by a large-scale ground invasion with the stated goal of destroying Hamas and controlling security in Gaza afterwards.[113] Israel killed tens of thousands of Palestinians, including civilians and combatants and displaced almost two million people.[114] South Africa accused Israel of genocide at the International Court of Justice and called for an immediate ceasefire.[115] The Court issued an order requiring Israel to take all measures to prevent any acts contrary to the 1948 Genocide Convention,[116][117][118] but did not order Israel to suspend its military campaign.[119]

The war spilled over, with Israel engaging in clashes with local militias in the West Bank, Hezbollah in Lebanon and northern Israel, and other Iranian-backed militias in Syria.[120][121][122] Iranian-backed militias also engaged in clashes with the United States,[123] while the Houthis blockaded the Red Sea in protest,[124] to which the United States responded with airstrikes in Yemen,[125] Iraq, and Syria.[126]

Attempts to reach a peaceful settlement

The PLO's participation in diplomatic negotiations was dependent on its complete disavowal of terrorism and recognition of Israel's "right to exist." This stipulation required the PLO to abandon its objective of reclaiming all of historic Palestine and instead focus on the 22 percent which came under Israeli military control in 1967.[127] By the late 1970s, Palestinian leadership in the occupied territories and most Arab states supported a two-state settlement.[128] In 1981, Saudi Arabia put forward a plan based on a two-state settlement to the conflict with support from the Arab League.[129] Israeli analyst Avner Yaniv describes Arafat as ready to make a historic compromise at this time, while the Israeli cabinet continued to oppose the existence of a Palestinian state. Yaniv described Arafat's willingness to compromise as a "peace offensive" which Israel responded to by planning to remove the PLO as a potential negotiating partner in order to evade international diplomatic pressure.[130] Israel would invade Lebanon the following year in an attempt to undermine the PLO as a political organization, weakening Palestinian nationalism and facilitating the annexation of the West Bank into Greater Israel.[89]

While the PLO had adopted a program of pursuing a Palestinian state alongside Israel since the mid-1970s, the 1988 Palestinian Declaration of Independence formally consecrated this objective. This declaration, which was based on resolutions from the Palestine National Council sessions in the late 1970s and 1980s, advocated for the creation of a Palestinian state comprising the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem, within the borders set by the 1949 armistice lines prior to 5 June 1967. Following the declaration, Arafat explicitly denounced all forms of terrorism and affirmed the PLO's acceptance of UN Resolutions 242 and 338, as well as the recognition of Israel's right to exist. All the conditions defined by Henry Kissinger for US negotiations with the PLO had now been met.[131]

Then-Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Shamir stood behind the stance that the PLO was a terrorist organization. He maintained a strict stance against any concessions, including withdrawal from occupied Palestinian territories, recognition of or negotiations with the PLO, and especially the establishment of a Palestinian state. Shamir viewed the U.S. decision to engage in dialogue with the PLO as a mistake that threatened the existing territorial status quo. He argued that negotiating with the PLO meant accepting the existence of a Palestinian state and hence was unacceptable.[132]

The peace process

The term "peace process" refers to the step-by-step approach to resolving the conflict. Having originally entered into usage to describe the US mediated negotiations between Israel and surrounding Arab countries, notably Egypt, the term "peace-process" has grown to be associated with an emphasis on the negotiation process rather than on presenting a comprehensive solution to the conflict.[133][134][135] As part of this process, fundamental issues of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict such as borders, access to resources, and the Palestinian right of return, have been left to "final status" talks. Such "final status" negotiations along the lines discussed in Madrid in 1991 have never taken place.[135]

The Oslo Accords of 1993 and 1995 built on the incremental framework put in place by the 1978 Camp David negotiations and the 1991 Madrid and Washington talks. The motivation behind the incremental approach towards a settlement was that it would "build confidence", but the eventual outcome was instead a dramatic decline in mutual confidence. At each incremental stage, Israel further entrenched its occupation of the Palestinian territories, despite the PA upholding its obligation to curbing violent attacks from extremist groups, in part by cooperating with Israeli forces.[136]

Meron Benvenisti, former deputy mayor of Jerusalem, observed that life became harsher for Palestinians during this period as state violence increased and Palestinian land continued to be expropriated as settlements expanded.[137][138][139][140] Israeli foreign minister Shlomo Ben-Ami described the Oslo Accords as legitimizing "the transformation of the West Bank into what has been called a 'cartographic cheeseboard'."[141]

Creation of the Palestinian Authority and security cooperation

Core to the Oslo Accords was the creation of the Palestinian Authority and the security cooperation it would enter into with the Israeli military authorities in what has been described as the "outsourcing" of the occupation to the PA.[127] Just before signing the Oslo accord, Rabin described the expectation that the "Palestinians will be better at establishing internal security than we were, because they will allow no appeals to the Sepreme Court and will prevent [human rights groups] from criticizing the conditions there."[142] Along these lines, Ben-Ami, who participated in the Camp David 2000 talks, described this process: "One of the meanings of Oslo was that the PLO was eventually Israel's collaborator in the task of stifling the Intifada and cutting short what was clearly an authentically democratic struggle for Palestinian independence."[141]

The Wye River Memorandum agreed on by the PA and Israel introduced a "zero tolerance" policy for "terror and violence." This policy was uniformly criticised by human rights organizations for its "encouragement" of human rights abuses.[143][144] Dennis Ross describes the Wye as having successfully reduced both violent and non-violent protests, both of which he considers to be "inconsistent with the spirit of Wye."[145] Watson claims that the PA frequently violated its obligations to curb incitement[146] and its record on curbing terrorism and other security obligations under the Wye River Memorandum was, at best, mixed.[147]

Oslo Accords (1993, 1995)

In 1993, Israeli officials led by Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian leaders from the Palestine Liberation Organization led by Yasser Arafat strove to find a peaceful solution through what became known as the Oslo peace process. A crucial milestone in this process was Arafat's letter of recognition of Israel's right to exist. Emblematic of the asymmetry in the Oslo process, Israel was not required to, and did not, recognize the right of a Palestinian state to exist. In 1993, the Declaration of Principles (or Oslo I) was signed and set forward a framework for future Israeli–Palestinian negotiations, in which key issues would be left to "final status" talks. The stipulations of the Oslo agreements ran contrary to the international consensus for resolving the conflict; the agreements did not uphold Palestinian self-determination or statehood and repealed the internationally accepted interpretation of UN Resolution 242 that land cannot be acquired by war.[138] With respect to access to land and resources, Noam Chomsky described the Oslo agreements as allowing "Israel to do virtually what it likes."[148] The Oslo process was delicate and progressed in fits and starts.

The process took a turning point at the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in November 1995 and the election of Netanyahu in 1996, finally unraveling when Arafat and Ehud Barak failed to reach an agreement at Camp David in July 2000 and later at Taba in 2001.[133][149] The interim period specified by Oslo had not built confidence between the two parties; Barak had failed to implement additional stages of the interim agreements and settlements expanded by 10% during his short term.[150] The disagreement between the two parties at Camp David was primarily on the acceptance (or rejection) of international consensus.[151][152] For Palestinian negotiators, the international consensus, as represented by the yearly vote in the UN General Assembly which passes almost unanimously, was the starting point for negotiations. The Israeli negotiators, supported by the American participants, did not accept the international consensus as the basis for a settlement.[153] Both sides eventually accepted the Clinton parameters "with reservations" but the talks at Taba were "called to a halt" by Barak, and the peace process itself came to a stand-still.[149] Ben-Ami, who participated in the talks at Camp David as Israel's foreign minister, would later describe the proposal on the table: "The Clinton parameters... are the best proof that Arafat was right to turn down the summit's offers".[151]

Camp David Summit (2000)

In July 2000, US President Bill Clinton convened a peace summit between Palestinian President Yasser Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak. Barak reportedly put forward the following as "bases for negotiation", via the US to the Palestinian President: a non-militarized Palestinian state split into 3–4 parts containing 87–92% of the West Bank after having already given up 78% of historic Palestine.[h] Thus, an Israeli offer of 91 percent of the West Bank (5,538 km2 of the West Bank translates into only 86 percent from the Palestinian perspective),[154] including Arab parts of East Jerusalem and the entire Gaza Strip,[155][156] as well as a stipulation that 69 Jewish settlements (which comprise 85% of the West Bank's Jewish settlers) would be ceded to Israel, no right of return to Israel, no sovereignty over the Temple Mount or any core East Jerusalem neighbourhoods, and continued Israel control over the Jordan Valley.[157][158]

Arafat rejected this offer,[155] which Palestinian negotiators, Israeli analysts and Israeli Foreign Minister Shlomo Ben-Ami described as "unacceptable".[149][159] According to the Palestinian negotiators the offer did not remove many of the elements of the Israeli occupation regarding land, security, settlements, and Jerusalem.[160]

After the Camp David summit, a narrative emerged, supported by Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and his foreign minister Shlomo Ben-Ami, as well as US officials including Dennis Ross and Madeleine Albright, that Yasser Arafat had rejected a generous peace offer from Israel and instead incited a violent uprising. This narrative suggested that Arafat was not interested in a two-state solution, but rather aimed to destroy Israel and take over all of Palestine. This view was widely accepted in US and Israeli public opinion. Nearly all scholars and most Israeli and US officials involved in the negotiations have rejected this narrative. These individuals include prominent Israeli negotiators, the IDF chief of staff, the head of the IDF's intelligence bureau, the head of the Shin Bet as well as their advisors.[161]

No tenable solution was crafted which would satisfy both Israeli and Palestinian demands, even under intense US pressure. Clinton has long blamed Arafat for the collapse of the summit.[162] In the months following the summit, Clinton appointed former US Senator George J. Mitchell to lead a fact-finding committee aiming to identify strategies for restoring the peace process. The committee's findings were published in 2001 with the dismantlement of existing Israeli settlements and Palestinian crackdown on militant activity being one strategy.[163]

Developments following Camp David

Following the failed summit Palestinian and Israeli negotiators continued to meet in small groups through August and September 2000 to try to bridge the gaps between their respective positions. The United States prepared its own plan to resolve the outstanding issues. Clinton's presentation of the US proposals was delayed by the advent of the Second Intifada at the end of September.[160]

Clinton's plan, eventually presented on 23 December 2000, proposed the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state in the Gaza Strip and 94–96 percent of the West Bank plus the equivalent of 1–3 percent of the West Bank in land swaps from pre-1967 Israel. On Jerusalem, the plan stated that "the general principle is that Arab areas are Palestinian and that Jewish areas are Israeli." The holy sites were to be split on the basis that Palestinians would have sovereignty over the Temple Mount/Noble sanctuary, while the Israelis would have sovereignty over the Western Wall. On refugees the plan suggested a number of proposals including financial compensation, the right of return to the Palestinian state, and Israeli acknowledgment of suffering caused to the Palestinians in 1948. Security proposals referred to a "non-militarized" Palestinian state, and an international force for border security. Both sides accepted Clinton's plan[160][164][165] and it became the basis for the negotiations at the Taba Peace summit the following January.[160]

Taba Summit (2001)

The Israeli negotiation team presented a new map at the Taba Summit in Taba, Egypt, in January 2001. The proposition removed the "temporarily Israeli controlled" areas, and the Palestinian side accepted this as a basis for further negotiation. With Israeli elections looming the talks ended without an agreement but the two sides issued a joint statement attesting to the progress they had made: "The sides declare that they have never been closer to reaching an agreement and it is thus our shared belief that the remaining gaps could be bridged with the resumption of negotiations following the Israeli elections." The following month the Likud party candidate Ariel Sharon defeated Ehud Barak in the Israeli elections and was elected as Israeli prime minister on 7 February 2001. Sharon's new government chose not to resume the high-level talks.[160]

Road map for peace (2002–2003)

One peace proposal, presented by the Quartet of the European Union, Russia, the United Nations and the United States on 17 September 2002, was the Road Map for Peace. This plan did not attempt to resolve difficult questions such as the fate of Jerusalem or Israeli settlements, but left that to be negotiated in later phases of the process. The proposal never made it beyond the first phase, whose goals called for a halt to both Israeli settlement construction and Israeli–Palestinian violence. Neither goal has been achieved as of November 2015.[166][167][168]

The Annapolis Conference was a Middle East peace conference held on 27 November 2007, at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, United States. The conference aimed to revive the Israeli–Palestinian peace process and implement the "Roadmap for peace".[169] The conference ended with the issuing of a joint statement from all parties. After the Annapolis Conference, the negotiations were continued. Both Mahmoud Abbas and Ehud Olmert presented each other with competing peace proposals. Ultimately no agreement was reached.[170][171]

Arab Peace Initiative (2002, 2007, 2017)

The Arab Peace Initiative (Arabic: مبادرة السلام العربية Mubādirat as-Salām al-ʿArabīyyah), also known as the Saudi Initiative, was first proposed by Crown Prince Abdullah of Saudi Arabia at the 2002 Beirut summit. The initiative is a proposed solution to the Arab–Israeli conflict as a whole, and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in particular.[172] The initiative was initially published on 28 March 2002, at the Beirut summit, and agreed upon again at the 2007 Riyadh summit. Unlike the Road Map for Peace, it spelled out "final solution" borders based on the UN borders established before the 1967 Six-Day War. It offered full normalization of relations with Israel, in exchange for the withdrawal of its forces from all the occupied territories, including the Golan Heights, to recognize "an independent Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital" in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, as well as a "just solution" for the Palestinian refugees.[173]

The Palestinian Authority led by Yasser Arafat immediately embraced the initiative.[174] His successor Mahmoud Abbas also supported the plan and officially asked U.S. President Barack Obama to adopt it as part of his Middle East policy.[175] Islamist political party Hamas, the elected government of the Gaza Strip, was deeply divided,[176] with most factions rejecting the plan.[177] Palestinians have criticised the Israel–United Arab Emirates normalization agreement and another with Bahrain signed in September 2020, fearing the moves weaken the Arab Peace Initiative, regarding the UAE's move as "a betrayal."[178]

The Israeli government under Ariel Sharon rejected the initiative as a "non-starter"[179] because it required Israel to withdraw to pre-June 1967 borders.[180] After the renewed Arab League endorsement in 2007, then-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert gave a cautious welcome to the plan.[181] In 2015, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu expressed tentative support for the Initiative,[182] but in 2018, he rejected it as a basis for future negotiations with the Palestinians.[183]

Current status

Apartheid

In July 2024, the International Court of Justice determined that Israeli policies violate the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.[184] As of 2022, all the major Israeli and international human rights organizations were in agreement that Israeli actions constituted the crime of apartheid.[185] In April 2021, Human Rights Watch released its report A Threshold Crossed, describing the policies of Israel towards Palestinians living in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza constituted the crime of apartheid.[186] A further report titled Israel's Apartheid Against Palestinians: Cruel System of Domination and Crime Against Humanity was released by Amnesty International on 1 February 2022.[187]

In 2018, the Knesset passed the Nation-State law which the Israeli legal group Adalah nicknamed the "Apartheid law." Adalah described the Nation-State law as "constitutionally enshrining Jewish supremacy and the identity of the State of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people." The Nation-State law is a Basic Law, meaning that it has "quasi-constitutional status,"[188] and states that the right to exercise national self-determination in Israel is "unique to the Jewish people".[189]

Occupied Palestinian territory

Israel has occupied the Palestinian territories, which comprise the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip, since the 1967 Six-Day War, making it the longest military occupation in modern history.[190] In 2024, the International Court of Justice determined that the Palestinian territories constitute one political unit and that Israel's occupation since 1967, and the subsequent creation of Israeli settlements and exploitation of natural resources, are illegal under international law. The court also ruled that Israel should pay full reparations to the Palestinian people for the damage the occupation has caused.[191][192]

Some Palestinians say they are entitled to all of the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem. Israel says it is justified in not ceding all this land, because of security concerns, and also because the lack of any valid diplomatic agreement at the time means that ownership and boundaries of this land is open for discussion.[193] Palestinians claim any reduction of this claim is a severe deprivation of their rights. In negotiations, they claim that any moves to reduce the boundaries of this land is a hostile move against their key interests. Israel considers this land to be in dispute and feels the purpose of negotiations is to define what the final borders will be. In 2017 Hamas announced that it was ready to support a Palestinian state on the 1967 borders "without recognising Israel or ceding any rights".[194]

Israeli settlements

The international community considers Israeli settlements to be illegal under international law,[195][196][197][198] but Israel disputes this.[199][200][201][202] Those who justify the legality of the settlements use arguments based upon Articles 2 and 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, as well as UN Security Council Resolution 242.[203][better source needed] The expansion of settlements often involves the confiscation of Palestinian land and resources, leading to displacement of Palestinian communities and creating a source of tension and conflict. Settlements are often protected by the Israeli military and are frequently flashpoints for violence against Palestinians. Furthermore, the presence of settlements and Jewish-only bypass roads creates a fragmented Palestinian territory, seriously hindering economic development and freedom of movement for Palestinians.[204] Amnesty International reports that Israeli settlements divert resources needed by Palestinian towns, such as arable land, water, and other resources; and, that settlements reduce Palestinians' ability to travel freely via local roads, owing to security considerations.[204]

As of 2023, there were about 500,000 Israeli settlers living in the West Bank, with another 200,000 living in East Jerusalem.[205][206][207] In February 2023, Israel's Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich took charge of most of the Civil Administration, obtaining broad authority over civilian issues in the West Bank.[208][209] In the first six months of 2023, 13,000 housing units were built in settlements, which is almost three times more than in the whole of 2022.[210]

Israeli military police

In a report published in February 2014 covering incidents over the three-year period of 2011–2013, Amnesty International stated that Israeli forces employed reckless violence in the West Bank, and in some instances appeared to engage in wilful killings which would be tantamount to war crimes. Besides the numerous fatalities, Amnesty said at least 261 Palestinians, including 67 children, had been gravely injured by Israeli use of live ammunition. In this same period, 45 Palestinians, including 6 children had been killed. Amnesty's review of 25 civilians deaths concluded that in no case was there evidence of the Palestinians posing an imminent threat. At the same time, over 8,000 Palestinians suffered serious injuries from other means, including rubber-coated metal bullets. Only one IDF soldier was convicted, killing a Palestinian attempting to enter Israel illegally. The soldier was demoted and given a 1-year sentence with a five-month suspension. The IDF answered the charges stating that its army held itself "to the highest of professional standards", adding that when there was suspicion of wrongdoing, it investigated and took action "where appropriate".[211][212]

Separation of the Gaza Strip

Since 2006, Israel has enforced an official and explicit policy of enforcing "separation" between the West Bank and Gaza Strip.[213] This separation policy has involved strict restrictions on imports, exports and travel to and from the Gaza Strip.[214] This policy began to develop as early as the 1950s, but was further formalized with the implementation of an Israeli closure regime in 1991, where Israel began requiring Gazans to obtain permits to exit the Gaza Strip and to enter the West Bank (cancelling the "general exit permit"). By treating the Gaza Strip as a separate entity, Israel has aimed to increase it's control over the West Bank while avoiding a political resolution to the conflict.[215][216] The lack of territorial contiguity between Gaza and the West Bank and the absence of any "safe passage" explain the success of Israel's policy of separation.[217] Harvard political economist Sara Roy describes the separation policy as motivated by Israeli rejection of territorial compromise, fundamentally undermining Palestinian political and economic cohesion and weakening national unity among Palestinians.[218][219]

The severing of Gaza from the West Bank hinterland reflects a paradigm shift in the framing of the conflict. After Hamas assumed power in 2007, Israel declared Gaza a "hostile territory," preferring to frame its obligations towards Gaza in terms of the law of armed conflict, over what it presented as a border dispute, as opposed to those of military occupation[217][220] (this framing was rebuffed by the ICJ in 2024 when the court stated that Israel continued to occupy the Gaza Strip even after the 2005 disengagement[221]). Indeed, the intensified blockade policy was presented by Israeli officials as "economic warfare" intended to "keep the Gazan economy on the brink of collapse" at the "lowest possible level."[217] Roy cites an Israeli Supreme Court's decision approving fuel cuts to Gaza as emblematic of the disabling of Gaza; the court deemed the fuel cuts permissible on the basis that they would not harm the population's "essential humanitarian needs."

The executive director of the Israeli human rights organization Gisha described Israeli policy towards Gaza between 2007 and 2010 as "explicitly punitive," controlling the entry of food based on calculated calorie needs to limit economic activity and enforce "economic warfare." These restrictions included allowing only small packets of margarine to prevent local food production. Gaza's GDP dramatically declined during this period as a result of these measures.[222] Indeed, by April 2010 Israel restricted the entry of commercial items to Gaza to a list of 73 products, compared with 4,000 products which had previously been approved. The result was the virtual collapse of Gaza's private sector, which Roy describes as largely completed after the 2008 Israeli Operation Cast Lead in Gaza.[218] According to Gisha, travel restrictions from the Gaza Strip are not based on individual security concerns, rather, the general rule is that travel to Israel or the West Bank from Gaza is not permitted other than in "exceptional" cases.[223] Israeli imposed travel restrictions aim in particular to prevent Gazans from living in the West Bank. Indeed, Israeli policy treats the Gaza Strip as a "terminus" station, with family reunification between the West Bank and Gaza Strip only possible if the family agrees to permanently relocate to the Gaza Strip.[224] The Israeli officials described the blockade as serving limited security value, instead referring to these restrictions as motivated by "political-security."[225]

Blockade of the Gaza Strip

Although closure has a long history in Gaza dating back to 1991 when it was first imposed, it was made more acute after 2000 with the start of the second intifada. Closure was tightened further after the 2005 disengagement and then again in 2006, after Hamas's electoral victory.[219] Heightened restrictions were imposed on imports and exports as well as on the movement of people, including Gaza's labor force. The total siege of Gaza that was imposed following the Hamas led attack on Israel during 7 October 2023, was part of that same policy of separation and closure, characterized by the destruction of Gaza's infrastructure (especially housing) and the denial of food, water, electricity, and fuel to its population.[217] On 9 October 2023, Israel declared war on Hamas and tightened its blockade of the Gaza Strip.[226] Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant declared, "There will be no electricity, no food, no fuel, everything is closed. We are fighting human animals and we are acting accordingly."[227][228]

Since its initiation, blockade has had a detrimental impact on the private sector in Gaza, the primary driver of economic growth in Gaza. Prior to the blockade, Gaza imported 95% of its inputs for manufacturing and exported 85% of the finished products (primarily to Israel and the West Bank). Employment in this sector dropped to 4% by 2010, with an overall unemployment rate of 40% at this time and 80% of the population living on less than 2 dollars a day.[229] Fewer than 40 commercial items were allowed in to the Gaza Strip by 2009, compared to a list of 4,000 items before the start of the blockade. Fuel imports were restricted such that 95% of Gaza's industrial operations were forced to close, with the rest operating far below capacity. In aggregate, 100,000 out of the 120,000 employed in the private sector lost their jobs as a result of the blockade. Most critically for the economy has been the near complete ban on exports from the Gaza Strip. The number of truckloads carrying exports fell to 2% their pre-blockade numbers. Only exports to the European market were allowed, a far less profitable market for Gazans than Israel and the West Bank. The products approved for export were primarily flowers and strawberries. The first export to the West Bank or Israel did not happen until 2012 and only in very limited quantities: up to four truckloads of furniture manufactured in Gaza were allowed through Israel for an exhibition in Amman.[219]

Even in the early years of Israeli imposed closure, the associated increased cost of doing business had a detrimental impact on trade. Goods transferred between the West Bank, Gaza, and Israel were required to be loaded onto Palestinian trucks initially and then off loaded onto Israeli trucks at the border even for distances of 50–100 miles. These increased costs include the costs for security checks, clearance, storage, and spoilage, as well as increased transportation costs.[230]

The Military Advocate General of Israel said that Israel is justified under international law to impose a blockade on an enemy for security reasons as Hamas "turned the territory under its de facto control into a launching pad of mortar and rocket attacks against Israeli towns and villages in southern Israel."[231] Media headlines have described a United Nations commission as ruling that Israel's blockade is "both legal and appropriate."[232][233] However, Amnesty International has stated that this is "completely false," and that the cited UN report made no such claim.[234] The Israeli Government's continued land, sea and air blockage is tantamount to collective punishment of the population, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.[235]

In January 2008, the Israeli government calculated how many calories per person were needed to prevent a humanitarian crisis in the Gaza Strip, and then subtracted eight percent to adjust for the "culture and experience" of the Gazans. Details of the calculations were released following Israeli human rights organization Gisha's application to the high court. Israel's Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories, who drafted the plan, stated that the scheme was never formally adopted, this was not accepted by Gisha.[236][237][238]

On 20 June 2010, in response to the Gaza flotilla raid, Israel's Security Cabinet approved a new system governing the blockade that would allow practically all non-military or dual-use items to enter the Gaza Strip. According to a cabinet statement, Israel would "expand the transfer of construction materials designated for projects that have been approved by the Palestinian Authority, including schools, health institutions, water, sanitation and more—as well as (projects) that are under international supervision."[239] Despite the easing of the land blockade, Israel will continue to inspect all goods bound for Gaza by sea at the port of Ashdod.[240] Despite these announcements, the economic situation did not substantially change and the virtual complete ban on exports remained in place. Only some consumer products and material for donor-sponsored projects was allowed in.[241]

United Nations and recognition of Palestinian statehood

The PLO have campaigned for full member status for the state of Palestine at the UN and for recognition on the 1967 borders. This campaign has received widespread support.[242][243] The UN General Assembly votes every year almost unanimously in favor of a resolution calling for the establishment of a Palestinian state on the 1967 borders.[244] The US and Israel instead prefer to pursue bilateral negotiation rather than resolving the conflict on the basis of international law.[245][246] Netanyahu has criticized the Palestinians of purportedly trying to bypass direct talks,[247] whereas Abbas has argued that the continued construction of Israeli-Jewish settlements is "undermining the realistic potential" for the two-state solution.[248] Although Palestine has been denied full member status by the UN Security Council,[249] in late 2012 the UN General Assembly overwhelmingly approved the de facto recognition of sovereign Palestine by granting non-member state status.[250]

Incitement

Following the Oslo Accords, which was to set up regulative bodies to rein in frictions, Palestinian incitement against Israel, Jews, and Zionism continued, parallel with Israel's pursuance of settlements in the Palestinian territories,[251] though under Abu Mazen it has reportedly dwindled significantly.[252] Charges of incitement have been reciprocal,[253][254] both sides interpreting media statements in the Palestinian and Israeli press as constituting incitement.[252] Schoolbooks published for both Israeli and Palestinian schools have been found to have encouraged a one-sided narrative and at times hatred of the other side.[255][256][257][258][259][260] Perpetrators of murderous attacks, whether against Israelis or Palestinians, often find strong vocal support from sections of their communities despite varying levels of condemnation from politicians.[261][262][263]

Both parties to the conflict have been criticized by third-parties for teaching incitement to their children by downplaying the other side's historical ties to the area, teaching propagandist maps, or indoctrinating their children to one day join the armed forces.[264][265]

Issues in dispute

The core issues of the conflict are borders, the status of settlements in the West Bank, the status of east Jerusalem, the Palestinian refugee right of return, and security.[134][138][266][267] With the PLO's recognition of Israel's "right to exist" in 1982,[148] the international community with the main exception of the United States and Israel[268][269] has been in consensus on a framework for resolving the conflict on the basis of international law.[270] Various UN bodies and the ICJ have supported this position;[270][134] every year, the UN General Assembly votes almost unanimously in favor of a resolution titled "Peaceful Settlement of the Question of Palestine." This resolution consistently affirms the illegality of the Israeli settlements, the annexation of East Jerusalem, and the principle of the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war. It also emphasizes the need for an Israeli withdrawal from the Palestinian territory occupied since 1967 and the need for a just resolution to the refugee question on the basis of UN resolution 194.[244]

Unilateral strategies and the rhetoric of hardline political factions, coupled with violence, have fostered mutual embitterment and hostility and a loss of faith in the possibility of reaching a peaceful settlement. Since the break down of negotiations, security has played a less important role in Israeli concerns, trailing behind employment, corruption, housing and other pressing issues.[271] Israeli policy had reoriented to focus on managing the conflict and the associated occupation of Palestinian territory, rather than reaching a negotiated solution.[271][272][139][273][274] The expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank has led the majority of Palestinians to believe that Israel is not committed to reaching an agreement, but rather to a pursuit of establishing permanent control over this territory in order to provide that security.[275]

Status of Jerusalem

In 1967, Israel unilaterally annexed East Jerusalem, in violation of international law. Israel seized a significant area further east of the city, eventually creating a barrier of Israeli settlements around the city, isolating Jerusalem's Palestinian population from the West Bank.[276] Israel's policy of constructing sprawling Jewish neighborhoods surrounding the Palestinian sections of the city were aimed at making a repartition of the city almost impossible. In a further effort to change the demography of Jerusalem in favor of a Jewish majority, Israel discouraged Palestinian presence in the city while encouraging Jewish presence, as a matter of policy. Specifically, Israel introduced policies restricting the space available for the construction of Palestinian neighborhoods, delaying or denying building permits and raising housing demolition orders.[277] Tensions in Jerusalem are primarily driven by provocations by Israeli authorities and Jewish extremists against Arabs in the city.[278]

The Israeli government, including the Knesset and Supreme Court, is located in the "new city" of West Jerusalem and has been since Israel's founding in 1948. After Israel annexed East Jerusalem in 1967, it assumed complete administrative control of East Jerusalem. Since then, various UN bodies have consistently denounced Israel's control over East Jerusalem as invalid.[277] In 1980, Israel passed the Jerusalem Law declaring "Jerusalem, complete and united, is the capital of Israel."[279][better source needed]

Many countries do not recognize Jerusalem as Israel's capital, with exceptions being the United States,[280] and Russia.[281] The majority of UN member states and most international organisations do not recognise Israel's claims to East Jerusalem which occurred after the 1967 Six-Day War, nor its 1980 Jerusalem Law proclamation.[282] The International Court of Justice in its 2004 Advisory opinion on the "Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory" described East Jerusalem as "occupied Palestinian territory".[283]

The three largest Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—hold Jerusalem as an important setting for their religious and historical narratives. Jerusalem is the holiest city in Judaism, being the former location of the Jewish temples on the Temple Mount and the capital of the ancient Israelite kingdom. For Muslims, Jerusalem is the third holiest site, being the location of the Isra' and Mi'raj event, and the Al-Aqsa Mosque. For Christians, Jerusalem is the site of Jesus' crucifixion and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Holy sites and the Temple Mount

Since the early 20th century, the issue of holy places and particularly the sacred places in Jerusalem has been employed by nationalist politicians.[284]

Israelis did not have access to the holy places in East Jerusalem during the period of Jordanian occupation.[285] Since 1975, Israel has banned Muslims from worshiping at Joseph's Tomb, a shrine considered sacred by both Jews and Muslims. Settlers established a yeshiva, installed a Torah scroll and covered the mihrab. During the Second Intifada Palestinian protesters looted and burned the site.[286][287] Israeli security agencies routinely monitor and arrest Jewish extremists that plan attacks, though many serious incidents have still occurred.[288] Israel has allowed almost complete autonomy to the Muslim trust (Waqf) over the Temple Mount.[277]

Palestinians have voiced concerns regarding the welfare of Christian and Muslim holy places under Israeli control.[289] Additionally, some Palestinian advocates have made statements alleging that the Western Wall Tunnel was re-opened with the intent of causing the mosque's collapse.[290]

Palestinian refugees

Palestinian refugees are people who lost both their homes and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 Arab–Israeli conflict[291] and the 1967 Six-Day War.[292] The number of Palestinians who were expelled or fled from Israel was estimated at 711,000 in 1949.[293] The descendants of all refugees (not just Palestinian refugees)[294] are considered by the UN to also be refugees. As of 2010 there are 4.7 million Palestinian refugees.[295] Between 350,000 and 400,000 Palestinians were displaced during the 1967 Arab–Israeli war.[292] A third of the refugees live in recognized refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The remainder live in and around the cities and towns of these host countries.[291] Most Palestinian refugees were born outside Israel and are not allowed to live in any part of historic Palestine.[291][296]

Israel has since 1948 prevented the return of Palestinian refugees and refused any settlement permitting their return except in limited cases.[148][297][298] On the basis of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and UN General Assembly Resolution 194, Palestinians claim the right of refugees to return to the lands, homes and villages where they lived before being driven into exile in 1948 and 1967. Arafat himself repeatedly assured his American and Israeli interlocutors at Camp David that he primarily sought the principle of the right of return to be accepted, rather than the full right of return, in practice.[299]

Palestinian and international authors have justified the right of return of the Palestinian refugees on several grounds:[300][301][302] Several scholars included in the broader New Historians argue that the Palestinian refugees fled or were chased out or expelled by the actions of the Haganah, Lehi and Irgun, Zionist paramilitary groups.[303][304] A number have also characterized this as an ethnic cleansing.[305][306][307][308] The New Historians cite indications of Arab leaders' desire for the Palestinian Arab population to stay put.[309]

The Israeli Law of Return that grants citizenship to people of Jewish descent has been described as discriminatory against other ethnic groups, especially Palestinians that cannot apply for such citizenship under the law of return, to the territory which they were expelled from or fled during the course of the 1948 war.[310][311][312]

According to the UN Resolution 194, adopted in 1948, "the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible."[313] UN Resolution 3236 "reaffirms also the inalienable right of the Palestinians to return to their homes and property from which they have been displaced and uprooted, and calls for their return".[314] Resolution 242 from the UN affirms the necessity for "achieving a just settlement of the refugee problem"; however, Resolution 242 does not specify that the "just settlement" must or should be in the form of a literal Palestinian right of return.[315]

Historically, there has been debate over the relative impact of the causes of the 1948 Palestinian exodus, although there is a wide consensus that violent expulsions by Zionist and Israeli forces were the main factor. Other factors include psychological warfare and Arab sense of vulnerability. Notably, historian Benny Morris states that most of Palestine's 700,000 refugees fled because of the "flail of war" and expected to return home shortly after a successful Arab invasion. He documents instances in which Arab leaders advised the evacuation of entire communities as happened in Haifa although recognizes that these were isolated events.[316][317] In his later work, Morris considers the displacement the result of a national conflict initiated by the Arabs themselves.[317] In a 2004 interview with Haaretz, he described the exodus as largely resulting from an atmosphere of transfer that was promoted by Ben-Gurion and understood by the military leadership. He also claimed that there "are circumstances in history that justify ethnic cleansing".[318] He has been criticized by political scientist Norman Finkelstein for having seemingly changed his views for political, rather than historical, reasons.[319]

Although Israel accepts the right of the Palestinian Diaspora to return into a new Palestinian state, Israel insists that the return of this population into the current state of Israel would threaten the stability of the Jewish state; an influx of Palestinian refugees would lead to the end of the state of Israel as a Jewish state since a demographic majority of Jews would not be maintained.[320][321][322]

Israeli security concerns

Throughout the conflict, Palestinian violence has been a concern for Israelis. Security concerns have historically been a key driver in Israeli political decision making, often expanding in scope and taking precedence over other considerations such as international law and Palestinian human rights.[323][324][325] The occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem and the continued expansion of settlements in those areas have been justified on security grounds.[326]

Israel,[327] along with the United States[328][better source needed] and the European Union, refer to any use of force by Palestinian groups as terroristic and criminal.[329][330][page needed] The United Nations General Assembly resolution A/RES/45/130 reflects an international consensus (113 out of 159 voting nations voted in favor, 13 voted against[331]) affirming Palestinians' legitimacy, as a people under foreign occupation, to use armed struggle to resist said occupation.[332]

In Israel, Palestinian suicide bombers have targeted civilian buses, restaurants, shopping malls, hotels and marketplaces.[333] From 1993 to 2003, 303 Palestinian suicide bombers attacked Israel.[citation needed] In 1994, Hamas initiated their first lethal suicide attack in response to the cave of the Patriarchs massacre where American-Israeli physician Baruch Goldstein opened fire in a mosque, killing 29 people and injuring 125.[334]

The Israeli government initiated the construction of a security barrier following scores of suicide bombings and terrorist attacks in July 2003. Israel's coalition government approved the security barrier in the northern part of the green line between Israel and the West Bank. According to the IDF, since the erection of the fence, terrorist acts have declined by approximately 90%.[335] The decline in attacks can also be attributed to the permanent presence of Israeli troops inside and around Palestinian cities and increasing security cooperation between the IDF and the Palestinian Authority during this period.[336] The barrier followed a route that ran almost entirely through land occupied by Israel in June 1967, unilaterally seizing more than 10% of the West Bank, including whole neighborhoods and settlement blocs, while splitting Palestinian villages in half with immediate effects on Palestinian's freedom of movement. The barrier, in some areas, isolated farmers from their fields and children from their schools, while also restricting Palestinians from moving within the West Bank or pursuing employment in Israel.[337][page needed][338][339]

In 2004 the International Court of Justice ruled that the construction of the barrier violated the Palestinian right to self-determination, contravened the Fourth Geneva Convention, and could not be justified as a measure of Israeli self-defense.[340] The ICJ further expressed that the construction of the wall by Israel could become a permanent fixture, altering the status quo. Israel's High Court, however, disagreed with the ICJ's conclusions, stating that they lacked a factual basis. Several human rights organizations, including B'Tselem, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International, echoed the ICJ's concerns. They suggested that the wall's route was designed to perpetuate the existence of settlements and facilitate their future annexation into Israel, and that the wall was a means for Israel to consolidate control over land used for illegal settlements. The sophisticated structure of the wall also indicated its likely permanence.[341]

Since 2001, the threat of Qassam rockets fired from Palestinian territories into Israel continues to be of great concern for Israeli defense officials.[342] In 2006—the year following Israel's disengagement from the Gaza Strip—the Israeli government claimed to have recorded 1,726 such launches, more than four times the total rockets fired in 2005.[327][343] As of January 2009, over 8,600 rockets have been launched,[344][345] causing widespread psychological trauma and disruption of daily life.[346] As a result of these attacks, Israelis living in southern Israel have had to spend long periods in bomb shelters. The relatively small payload carried on these rockets, Israel's advanced early warning system, American-supplied anti-missile capabilities, and network of shelters made the rockets rarely lethal. In 2014, out of 4,000 rockets fired from the Gaza Strip, only six Israeli civilians were killed. For comparison, the payload carried on these rockets is smaller than Israeli tank shells, of which 49,000 were fired in Gaza in 2014.[347]

There is significant debate within Israel about how to deal with the country's security concerns. Options have included military action (including targeted killings and house demolitions of terrorist operatives), diplomacy, unilateral gestures toward peace, and increased security measures such as checkpoints, roadblocks and security barriers. The legality and the wisdom of all of the above tactics have been called into question by various commentators.[citation needed]

Since mid-June 2007, Israel's primary means of dealing with security concerns in the West Bank has been to cooperate with and permit United States-sponsored training, equipping, and funding of the Palestinian Authority's security forces, which with Israeli help have largely succeeded in quelling West Bank supporters of Hamas.[348]

Water resources

In the Middle East, water resources are of great political concern. Since Israel receives much of its water from two large underground aquifers which continue under the Green Line, the use of this water has been contentious in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Israel withdraws most water from these areas, but it also supplies the West Bank with approximately 40 million cubic metres annually, contributing to 77% of Palestinians' water supply in the West Bank, which is to be shared for a population of about 2.6 million.[349]

While Israel's consumption of this water has decreased since it began its occupation of the West Bank, it still consumes the majority of it: in the 1950s, Israel consumed 95% of the water output of the Western Aquifer, and 82% of that produced by the Northeastern Aquifer. Although this water was drawn entirely on Israel's own side of the pre-1967 border, the sources of the water are nevertheless from the shared groundwater basins located under both West Bank and Israel.[350]

In the Oslo II Accord, both sides agreed to maintain "existing quantities of utilization from the resources." In so doing, the Palestinian Authority established the legality of Israeli water production in the West Bank, subject to a Joint Water Committee (JWC). Moreover, Israel obligated itself in this agreement to provide water to supplement Palestinian production, and further agreed to allow additional Palestinian drilling in the Eastern Aquifer, also subject to the Joint Water Committee.[351][352] The water that Israel receives comes mainly from the Jordan River system, the Sea of Galilee and two underground sources. According to a 2003 BBC article the Palestinians lack access to the Jordan River system.[353]

According to a report of 2008 by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, water resources were confiscated for the benefit of the Israeli settlements in the Ghor. Palestinian irrigation pumps on the Jordan River were destroyed or confiscated after the 1967 war and Palestinians were not allowed to use water from the Jordan River system. Furthermore, the authorities did not allow any new irrigation wells to be drilled by Palestinian farmers, while it provided fresh water and allowed drilling wells for irrigation purposes at the Jewish settlements in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.[354]

A report was released by the UN in August 2012 and Max Gaylard, the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator in the occupied Palestinian territory, explained at the launch of the publication: "Gaza will have half a million more people by 2020 while its economy will grow only slowly. In consequence, the people of Gaza will have an even harder time getting enough drinking water and electricity, or sending their children to school". Gaylard present alongside Jean Gough, of the UN Children's Fund (UNICEF), and Robert Turner, of the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). The report projects that Gaza's population will increase from 1.6 million people to 2.1 million people in 2020, leading to a density of more than 5,800 people per square kilometre.[355]

Future and financing

Numerous foreign nations and international organizations have established bilateral agreements with the Palestinian and Israeli water authorities. It was estimated that a future investment of about US$1.1bn for the West Bank and $0.8bn for the Gaza Strip Southern Governorates was needed for the planning period from 2003 to 2015.[356]

In late 2012, a donation of $21.6 million was announced by the Government of the Netherlands—the Dutch government stated that the funds would be provided to the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), for the specific benefit of Palestinian children. An article, published by the UN News website, stated that: "Of the $21.6 million, $5.7 will be allocated to UNRWA's 2012 Emergency Appeal for the occupied Palestinian territory, which will support programmes in the West Bank and Gaza aiming to mitigate the effects on refugees of the deteriorating situation they face."[355]

Agricultural rights

The conflict has been about land since its inception.[357] When Israel became a state after the war in 1948, 77% of Palestine's land was used for the creation on the state.[358] The majority of those living in Palestine at the time became refugees in other countries and this first land crisis became the root of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[359][page needed] Because the root of the conflict is with land, the disputes between Israel and Palestine are well-manifested in the agriculture of Palestine.