Dennis Hastert

Dennis Hastert | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2005 | |

| 51st Speaker of the United States House of Representatives | |

| In office January 6, 1999 – January 3, 2007 | |

| Preceded by | Newt Gingrich |

| Succeeded by | Nancy Pelosi |

| Leader of the House Republican Conference | |

| In office January 6, 1999 – January 3, 2007 | |

| Preceded by | Newt Gingrich |

| Succeeded by | John Boehner |

| House Republican Chief Deputy Whip | |

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 3, 1999 | |

| Leader | Newt Gingrich |

| Preceded by | Bob Walker |

| Succeeded by | Roy Blunt |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Illinois's 14th district | |

| In office January 3, 1987 – November 26, 2007 | |

| Preceded by | John Grotberg |

| Succeeded by | Bill Foster |

| Member of the Illinois House of Representatives from the 82nd district | |

| In office January 1983 – January 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Edward Petka |

| Member of the Illinois House of Representatives from the 39th district | |

| In office January 1981 – January 1983 Serving with Suzanne L. "Sue" Deuchler, Lawrence "Laz" Murphy | |

| Preceded by | William L. Kempiners Allan L. "Al" Schoeberlein |

| Succeeded by | Kenneth C. Cole |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Dennis Hastert January 2, 1942 Aurora, Illinois, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Jean Kahl (m. 1973) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | North Central College Wheaton College, Illinois (BA) Northern Illinois University (MS) |

| Signature |  |

John Dennis Hastert (/ˈhæstərt/ HASS-tərt; born January 2, 1942) is an American former politician, teacher, and wrestling coach who represented Illinois's 14th congressional district from 1987 to 2007 and served as the 51st Speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1999 to 2007.[1] Hastert was the longest-serving Republican Speaker of the House in history. After Democrats gained a majority in the House in 2007, Hastert resigned and began work as a lobbyist. In 2016, he was sentenced to 15 months in prison for financial offenses related to the sexual abuse of teenage boys.[2][3]

From 1965 to 1981, Hastert was a high school teacher and coach at Yorkville High School in Yorkville, Illinois. He lost a 1980 bid for the Illinois House of Representatives but ran again and won a seat in 1981. He was first elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1986 and was re-elected every two years until he retired in 2007. Hastert rose through the Republican ranks in the House, becoming chief deputy whip in 1995 and speaker in 1999. As Speaker of the House, Hastert supported the George W. Bush administration's foreign and domestic policies. After Democrats took control of the House in 2007 following the 2006 elections, Hastert declined to seek the position of minority leader, resigned his House seat, and became a lobbyist at the firm of Dickstein Shapiro.

In May 2015, Hastert was indicted on federal charges of structuring bank withdrawals to evade bank reporting requirements and making false statements to federal investigators. Federal prosecutors said that the funds withdrawn by Hastert were used as hush money to conceal his past sexual misconduct.[4][3] In October 2015, Hastert entered into a plea agreement with prosecutors. Under the agreement, Hastert pleaded guilty to the structuring charge (a felony); the charge of making false statements was dropped.[5] In court submissions filed in April 2016, federal prosecutors alleged that Hastert had molested at least four boys as young as 14 years of age during his time as a high school wrestling coach.[2] At a sentencing hearing, Hastert admitted that he had sexually abused boys whom he had coached.[6] Referring to Hastert as a "serial child molester", a federal judge imposed a sentence of 15 months in prison, two years' supervised release, and a $250,000 fine.[3][7] Hastert was imprisoned in 2016 and was released 13 months later;[8] he became the highest-ranking elected official in U.S. history to serve a prison sentence.[3]

Early life and early career

[edit]Hastert was born on January 2, 1942, in Aurora, Illinois, the eldest of two sons of Naomi (née Nussle) and Jack Hastert.[9][10] Hastert is of Luxembourgish and Norwegian descent on his father's side, and of German descent on his mother's.[11]

Hastert grew up in a rural Illinois farming community. His middle-class family owned a farm supply business and a family farm; Hastert bagged and hauled feed and performed farm chores.[10][12] As a young man, Hastert also worked shifts in the family's Plainfield restaurant, The Clock Tower, where he was a fry cook.[10][13] Hastert became a born-again Christian as a teenager, during his sophomore year of high school.[10][14] Hastert attended Oswego High School, where he was a star wrestler and football player.[10][12]

Hastert briefly attended North Central College, but later transferred to Wheaton College, a Christian liberal arts college.[12] Jim Parnalee, Hastert's roommate at North Central who transferred with him to Wheaton, was a Marine Corps Reserve member who in 1965 became the school's first student to be killed in Vietnam. Hastert continued to visit Parnalee's family each year in Michigan.[12][14] Because of a wrestling injury, Hastert never served in the military. In 1964, Hastert graduated from Wheaton with a B.A. in economics.[10][12][15] In 1967, he received his M.S. in philosophy of education from Northern Illinois University (NIU).[10][15] In his first year of graduate school, Hastert spent three months in Japan as part of the People to People Student Ambassador Program.[16] One of Hastert's fellow group members was Tony Podesta (then the president of the Young Democrats at University of Illinois at Chicago Circle).[16]

Hastert was employed by Yorkville Community Unit School District 115 for 16 years, from 1965 to 1981.[17] Hastert began working there, at age 23, while still attending NIU.[10] Throughout that time, Hastert worked as a teacher at Yorkville High School (teaching government, history, economics, and sociology), where he also served as a football and wrestling coach.[10][18] Hastert led the school's wrestling team to the 1976 state title and was later named Illinois Coach of the Year.[10] According to federal prosecutors, during the time that he coached wrestling, Hastert sexually abused at least four of his students.[19]

Hastert was a Boy Scout volunteer with Explorer Post 540 of Yorkville for 17 years, during his time as a schoolteacher and coach.[20] Hastert reportedly traveled with the Explorers on trips to the Grand Canyon, the Bahamas, Minnesota, and the Green River in Utah.[20][21]

In 1973, Hastert married a fellow teacher at the high school, Jean Kahl, with whom he had two sons.[12]

Illinois House of Representatives

[edit]Hastert considered applying to become an assistant principal at the school, but then decided to enter politics, although at the time "he knew nothing about politics."[10] Hastert approached Phyllis Oldenburg, a Republican operative in Kendall County, seeking advice on running for a seat in the Illinois Legislature.[10]

Hastert lost a 1980 Republican primary for the Illinois House of Representatives, but showed a talent for campaigning, and after the election, volunteered for an influential state senator, John E. Grotberg.[10] In the summer of 1980, however, State Representative Al Schoeberiein had become terminally ill, and local Republican party officials selected Hastert as the successor over two major rivals, lawyer Tom Johnson of West Chicago and Mayor Richard Verbic of Elgin.[12][14] The first round of balloting resulted in a tie, but Hastert was chosen after Grotberg interceded on Hastert's behalf.[12] Hastert, fellow Republican Suzanne Deuchler and Democratic incumbent Lawrence Murphy were elected that year.[22]

Hastert served three terms in the state House from the 82nd district,[14][23] where he served on the Appropriations Committee.[12] According to a 1999 Chicago Tribune profile, in the state House "Hastert quickly staked out a place on the far right of the political spectrum, once earning a place on the 'Moral Majority Honor Roll.' Yet, he also displayed yeoman-like work habits and an ability to put aside partisanship."[14] He gained a reputation as a dealmaker and party leader known for "asking his colleagues to write their spending requests on a notepad so he could carry them into negotiating sessions" and holding early-morning pre-meetings to organize talking points.[12] One of his first moves in the House was to help block passage of the Equal Rights Amendment; the state House Speaker George Ryan appointed Hastert to a committee that worked to prevent the ERA from coming to the House floor.[14] In the state House, Hastert opposed bills barring discrimination against gays; supported (unsuccessfully) proposals to raise the driving age to 18; and voted for a mandatory seat belt law, although he later voted to repeal it.[14]

In 1986, at the urging of Governor James R. Thompson, Hastert developed a plan to deregulate Illinois utility companies.[14] Under the plan developed by Hastert and Republican staffers, property and gross-receipts taxes that utilities paid would be eliminated and replaced with a "state service tax" that service-industry businesses (ranging from insurers to funeral homes) would pay.[14] Critics of the plan said that it was too favorable to utility companies, and the proposal was not adopted.[14]

U.S. House of Representatives

[edit]Meanwhile, Hastert's political mentor Grotberg had been elected to Congress as the representative from Illinois's 14th district, which covered a swath of exurban territory west of Chicago. Grotberg was diagnosed with cancer in 1986, and was unable to run for a second term.[10][12] Hastert was nominated to replace him; in the general election in November 1986, he defeated Democratic candidate Mary Lou Kearns, the Kane County coroner, in a relatively close race.[10][12]

Hastert was then reelected in his Fox Valley-centered district several times, by wider margins, aided by his role in redistricting following the 1990 Census.[12]

Following the House banking scandal, which broke in 1992, it was revealed that Hastert had bounced 44 checks during the period under investigation.[14][24] A Justice Department special counsel said there was no reason to believe Hastert had committed any crime in overdrawing his accounts.[24]

As a protégé of House Minority Leader Robert H. Michel, Hastert rose through the Republican ranks in the House, and in 1995 (after the Republicans gained control of the House and Newt Gingrich became Speaker), Hastert became chief deputy whip.[12] Michel appointed Hastert to the Republicans' health care task force,[14] where Hastert became a "prominent voice" in helping defeat the Clinton health care plan of 1993.[25][26]

Hastert developed a close relationship with Tom DeLay, the House majority whip, and was widely seen as DeLay's deputy.[12] Hastert and DeLay first worked together in 1989, on Edward Madigan's unsuccessful race against Gingrich for minority whip. Hastert later managed DeLay's successful campaign to become whip.[12] In September 1998, the two added an extra $250,000 to the Defense Department appropriations bill for "pharmacokinetics research" which paid for an Army experiment with nicotine chewing gum manufactured by the Amurol Confections Company in Yorkville, in Hastert's district.[12][27] On the House floor, Democratic Representative Peter DeFazio criticized the insertion of the provision; Hastert defended it.[27] Hastert played "good cop" to DeLay's "bad cop."[28][29]

On the eve of his elevation to Speaker, Hastert was described as "deeply conservative at heart" by the Associated Press.[30] The AP reported: "He is an evangelical Christian who opposes abortion and advocates lower taxes, a balanced-budget amendment to the Constitution and the death penalty. He spearheaded the GOP's fight against using sampling techniques to take the next census. Such groups as the National Right to Life Committee, the Christian Coalition, the Chamber of Commerce and the NRA Political Victory Fund all gave his voting record perfect scores of 100. The American Conservative Union gave him an 88. Meanwhile, the liberal Americans for Democratic Action, the American Civil Liberties Union and labor organizations such as the AFL–CIO and the Teamsters each gave Hastert zero points. The League of Conservation Voters rated him a 13."[30]

Hastert criticized the Clinton administration's plans to conduct the 2000 Census using sampling techniques.[12] Hastert was a supporter of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and in 1993 voted to approve the trade pact.[31] He was a gun rights supporter who voted against the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act and Federal Assault Weapons Ban.[14]

Hastert was the "House Republicans' leader on anti-narcotics efforts"[30] and was a strong supporter of the War on Drugs.[12][32] In this role, he campaigned to bar needle-exchange programs from receiving federal funds,[30] and criticized the Clinton administration for what he believed was insufficient funding for drug interdiction efforts.[12][32]

In redistricting following the 2000 census, Hastert brokered a deal with Democratic Representative William Lipinski, also from Illinois, that "protected the reelection prospects of almost every Illinois incumbent."[33] The deal easily passed the divided Illinois Legislature.[33]

Committee assignments and House positions

[edit]Hastert served on the following House committees and in the following House positions. (This list does not include subcommittee assignments or positions within the Republican Conference).

- 100th Congress (1987–1989) – Government Operations; Public Works and Transportation[34][35]

- 101st Congress (1989–1991) – Government Operations; Public Works and Transportation; Select Committee on Children, Youth, and Families[36]

- 102nd Congress (1991–1993) – Energy and Commerce; Government Operations; Hunger[37]

- 103rd Congress (1993–1995) – Energy and Commerce; Government Operations[38]

- 104th Congress (1995–1997) – Chief Deputy Majority Whip; Commerce; Government Reform and Oversight[39]

- 105th Congress (1997–1999) – Chief Deputy Majority Whip; Commerce; Government Reform and Oversight[40]

- 106th Congress (1999–2001) – The Speaker; Joint Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies[41]

- 107th Congress (2001–2003) – The Speaker[42]

- 108th Congress (2003–2005) – The Speaker; Intelligence (ex officio)[43]

- 109th Congress (2005–2007) – The Speaker; Intelligence (ex officio)[44]

Speaker of the House

[edit]

In the aftermath of the 1998 midterm elections, where the GOP lost five House seats and failed to make a net gain of seats in the Senate, House Speaker Newt Gingrich of Georgia stepped down from the speakership and declined to take his seat for an 11th term. In mid-December, Representative Robert L. Livingston of Louisiana—the former chairman of the House Appropriations Committee and the Speaker-designate—stated in a dramatic surprise announcement on the House floor that he would not become Speaker, following widely publicized revelations of his extramarital affairs.[25][45][46]

Although he reportedly had no warning of Livingston's decision to step aside, Hastert "began lobbying on the House floor within moments" of Livingston's announcement, and by the afternoon of that day had secured the public backing of the House Republican leadership, including Gingrich, DeLay (who was "viewed as too partisan to step into the role of Speaker") and Dick Armey (who was "viewed as too weak" and was damaged by party infighting).[25][46] On that day, Hastert was endorsed by about 100 Republican representatives, ranging from conservatives such as Steve Largent to moderates such as Mike Castle, for the speakership.[46] Representative Christopher Cox of California, viewed as a potential rival, decided by evening not to challenge Hastert for the speakership.[46] Hastert became known as "the Accidental Speaker."[47][48]

In accepting the position, Hastert broke the tradition that the new speaker deliver his first address from the speaker's chair, instead delivering his 17-minute acceptance speech from the floor.[49] Hastert adopted a conciliatory tone and pledged to work for bipartisanship, saying that: "Solutions to problems cannot be found in a pool of bitterness."[49][50]

Nevertheless, in November 2004, Hastert instituted what became known as the Hastert Rule (or "majority of the majority" rule), which was an informal, self-imposed political practice of allowing the House to vote on only those bills that were supported by the majority of its Republican members. The practice received criticism as an unduly partisan measure both at the time it was adopted and in the subsequent years.[51][52] The same year, the Hastert aide who coined the phrase also stated that the structure was not workable.[53] In any case, a number of bills subsequently passed the House without the support of a majority of the majority party in the House, as shown by a list compiled by The New York Times.[54] In 2013, after leaving office, Hastert disowned the policy, saying that "there is no Hastert Rule" and that the "rule" was more of a principle that the majority party should follow its own policies.[55]

Congressional expert Norm Ornstein writes that Hastert "blew up" the House's "regular order," which is "a mix of rules and norms that allows debate, deliberation, and amendments in committees and on the House floor, that incorporates and does not shut out the minority (even if it still loses most of the time), that takes bills that pass both houses to a conference committee to reconcile differences, [and] that allows time for members and staff to read, digest, and analyze bills."[56] Ornstein commented that "no speaker did more to relegate the regular order to the sidelines than Hastert. ... The House is a very partisan institution, with rules structured to give even tiny majorities enormous leverage. But Hastert took those realities to a new and more tribalized, partisan plane."[56] Despite this shift, Hastert was widely seen as "affable" and low-key; he did not seek the limelight, "become a regular on Sunday talk shows or anything close to a household word or figure," or "openly exhibit the kind of snarling or mean partisan demeanor that made Tom DeLay such a mark of hatred for Democrats."[56]

Hastert adopted a much lower profile in the media than conventional wisdom would suggest for a Speaker. This led to accusations that he was only a figurehead for DeLay.[57] In 2005, DeLay was indicted by a Texas grand jury on charges of campaign finance violations. DeLay stepped down as majority leader and was replaced in that post by Roy Blunt; DeLay resigned from Congress the following year.[58][59]

Throughout his term, Hastert was a strong supporter of President George W. Bush's foreign and domestic policies. Hastert was described as a Bush loyalist who worked closely with the White House to shepherd Bush's agenda through Congress,[10][60] The two frequently praised each other, expressed mutual respect, and had a close working relationship, even during the controversy over Representative Mark Foley sending sexually explicit text messages to teenage male pages.[61][62] Hastert even provided Vice President Dick Cheney office space inside the House in the United States Capitol.[63] In 2003, Hastert and Bush met privately at the White House about twice a month to discuss congressional developments.[62]

Earmarks—line-item projects inserted into appropriations bills at the request of individual members, and often referred to as "pork-barrel" spending—"exploded under [Hastert's] leadership," growing from $12 billion in 1999 (at the beginning of Hastert's term) to an all-time high of $29 billion in 2006 (Hastert's last year as speaker).[47] Hastert himself made earmarks a personal trademark; from 1999 to May 2005, Hastert obtained $24 million in federal earmarked grant funds to groups and institutions in Aurora, Illinois, Hastert's birthplace and his district's largest city.[64]

106th Congress

[edit]In March 1999, soon after Hastert's elevation to the speakership, the Washington Post, in a front-page story, reported that Hastert "has begun offering industry lobbyists the kind of deal they like: private audiences where, for a price, they can voice their views on what kind of agenda the 106th Congress should pursue."[65] Hastert's style and extensive fundraising led Common Cause to critique the "pay-to-play system" in Congress.[65]

Hastert was known as a frequent critic of Bill Clinton, and immediately upon assuming the speakership, he "played a lead role" in the impeachment of the president.[66] Nevertheless, Hastert and the Clinton administration did work together on several initiatives, including the New Markets Tax Credit Program and Plan Colombia.[25]

In 2000, Hastert announced he would support an Armenian genocide resolution. Analysts noted that at the time there was a tight congressional race in California, in which might be important to have the large Armenian community in favor of the Republican incumbent. The resolution, vehemently opposed by Turkey, had passed the Human Rights Subcommittee of the House and the International Relations Committee, but Hastert, although first supporting it, withdrew the resolution on the eve of the full House vote. He explained this by saying that he had received a letter from Clinton asking him to withdraw it because it would harm U.S. interests.[67] Even though there is no evidence that a payment was made, an official at the Turkish Consulate is said to have claimed in a recording that was translated by Sibel Edmonds that the price for Hastert to withdraw the Armenian genocide resolution would have been at least $500,000.[68][69]

107th Congress

[edit]

"Hastert and the senior Republican leadership in the House were able to maintain party discipline to a great degree", which allowed them to regularly enact legislation, despite a narrow majority (less than 12 seats) in the 106th and 107th Congresses.[70] Hastert was a strong supporter of the Iraq War Resolution and the ensuing 2003 invasion of Iraq and the Iraq War. Hastert stated in the House in October 2002 that he believed there was "a direct connection between Iraq and al-Qaeda" and that the U.S. should "do all that we can to disarm Saddam Hussein's regime before they provide al-Qaeda with weapons of mass destruction."[71] In a February 2003 interview with the Chicago Tribune, Hastert "launched into a lengthy and passionate denunciation" of France's resistance to the Iraq war and stated that he wanted to go "nose-to-nose" with the country.[72] In 2006, Hastert visited Iraq at Bush's request and supported a supplemental Iraq War spending bill.[73]

As Speaker, Hastert shepherded the USA Patriot Act in October 2001 to passage in the House on a 357–66 vote.[74] In a 2011 interview, Hastert claimed credit for its passage over the misgivings of many members.[74] Fourteen years later, federal prosecutors used the Patriot Act's expansion of currency transaction reporting requirements to indict Hastert on federal charges.[74]

As speaker, Hastert also oversaw the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, a major education bill; the Bush tax cuts in 2001 and 2003 legislation; and the Homeland Security Act of 2002, which reorganized the government and created the Department of Homeland Security.[70] Although Hastert was successful in implementing Bush policy priorities, during his tenure the House also "regularly passed conservative bills only to have them blocked in the more moderate Senate."[70] One such bill was an energy bill, backed by the Bush administration, which would have authorized drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge; this provision was killed in the Senate.[70]

Hastert opposed the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (McCain-Feingold), the landmark campaign finance reform law.[30] In 2001, during the debate on the bill, Hastert criticized Republican Senator John McCain, the bill's cosponsor, saying that McCain had "bullied" House Republicans by sending them letters in support of his campaign-finance reform proposals.[75] Hastert called the legislation "the worst thing that ever happened to Congress"[76] and expressed the view that there were "constitutional flaws" in the legislation.[77] Supporters of campaign-finance reform circumvented Hastert by means of a discharge petition, a seldom-used procedural mechanism in which a measure may be brought to a floor vote (over the objections of the speaker) if an absolute majority of Representatives sign a petition in support of doing so.[47] The discharge petition was not successfully used again[78] until 2015.[79]

108th Congress

[edit]In 2004, Hastert again feuded with McCain amid conflict between the House and the Senate over the 2005 budget.[80] After "McCain gave a speech excoriating both political parties for refusing to sacrifice their tax cutting and spending agendas in wartime," Hastert publicly questioned McCain's "credentials as a Republican and suggested that the decorated Vietnam War veteran did not understand the meaning of sacrifice."[80]

Hastert was key to the passage in November 2003 of key Medicare legislation which created Medicare Part D, a prescription drug benefit.[81] Hastert's push to pass the legislation—culminating in a three-hour House vote in which the Speaker, "an imposing former wrestling coach, was literally leaning on recalcitrant lawmakers to win their support"—raised the Speaker's profile and contributed to a shift of his image from amiable and low-key to more forceful.[81] The extension of the vote for hours and the arm-twisting of members brought condemnation of Hastert from Democrats, with House Minority Whip Steny H. Hoyer saying: "They are corrupting the practices of the House."[81] The bill passed on a narrow vote of 220 to 215.[82]

In 2004, Hoyer called upon Hastert to initiate a House Ethics Committee investigation into statements by Representative Nick Smith, a Republican of Michigan, who stated that groups and lawmakers had offered support for his son's campaign for Congress in exchange for Smith's support of the Medicare bill.[82] In October 2004, the House Ethics Committee admonished DeLay for pressuring Smith on the Medicare prescription-drug bill, but stated that DeLay did not break the law or House ethics rules.[83] Hastert issued a statement supporting DeLay, but the admonishment was viewed as harming DeLay's chances of succeeding Hastert as Speaker.[83]

109th Congress

[edit]On October 27, 2005, Hastert became the first Speaker to author a blog.[84] On "Speaker's Journal" on his official U.S. House website, Hastert wrote in his first post: "This is Denny Hastert and welcome to my blog. This is new to me. I can't say I'm much of a techie. I guess you could say my office is teaching the old guy new tricks. But I'm excited. This is the future. And it is a new way for us to get our message out."[85]

On June 1, 2006, Hastert became the longest-serving Republican Speaker of the House in history, surpassing the record previously held by fellow Illinoisan Joseph Gurney Cannon, who held the post from November 1903 to March 1911.[86][87]

In 2005, following Hurricane Katrina, Hastert told an Illinois newspaper that "It looks like a lot of that place [referring to New Orleans] could be bulldozed" and stated that spending billions of dollars to rebuild the devastated city "doesn't make sense to me."[88] The remarks enraged Governor Kathleen Blanco of Louisiana, who stated that Hastert's comments were "absolutely unthinkable for a leader in his position" and demanded an immediate apology.[88] Former President Bill Clinton, responding to the remarks, stated that had they been in the same place when the remarks were made, "I'm afraid I would have assaulted him."[88] After the remarks caused a furor, Hastert issued a statement saying he was not "advocating that the city be abandoned or relocated" and later issued another statement saying that "Our prayers and sympathies continue to be with the victims of Hurricane Katrina."[88] Hastert was also criticized for being absent from the Capitol during the approval of a $10.5 billion Katrina relief plan; Hastert was in Indiana attending a colleague's fundraiser and an antique car auction. Hastert later said that he donated the proceeds from one of the antique cars he sold at the auction to hurricane relief efforts.[88]

Ethics

[edit]When the United States House Committee on Ethics recommended a series of reprimands against Majority Leader Tom DeLay, Hastert fired committee Chairman Joel Hefley, (R-CO), as well as committee members Kenny Hulshof, (R-MO) and Steve LaTourette, (R-OH).[56] After DeLay's associates were indicted, Hastert enacted a new rule allowing DeLay to keep the majority leadership even if DeLay himself was indicted.[56]

A September 2005 article in Vanity Fair revealed that during her work, former FBI translator Sibel Edmonds had heard Turkish wiretap targets boast of covert relations with Hastert. The article states, "the targets reportedly discussed giving Hastert tens of thousands of dollars in surreptitious payments in exchange for political favors and information."[68] A spokesman for Hastert later denied the claims, relating them to the Jennifer Aniston–Brad Pitt breakup.[89] Following his congressional career, Hastert received a $35,000 per month contract lobbying on behalf of Turkey.[90]

In December 2006, the House Ethics Committee determined that Hastert and other congressional leaders were "willfully ignorant" in responding to early warnings of the Mark Foley congressional page scandal, but did not violate any House rules.[91][92] In a committee statement, Kirk Fordham, who was Foley's chief of staff until 2005, said that he had alerted Scott B. Palmer, Hastert's chief of staff, to Foley's inappropriate advances toward congressional pages in 2002 or 2003, asking congressional leadership to intervene.[92] Then-House Majority Leader John Boehner and National Republican Congressional Committee chair Thomas M. Reynolds stated that they told Hastert about Foley's conduct in spring 2005.[92] A Hastert spokesman stated that "what Kirk Fordham said did not happen."[92] Hastert also stated that he could not recall conversations with Boehner and Reynolds, and that he did not learn of Foley's conduct until late September 2006, when the affair became public.[92]

In 2006, Hastert became embroiled in controversy over his championing of a $207 million earmark (inserted in the 2005 omnibus highway bill) for the Prairie Parkway, a proposed expressway running through his district.[93][94][95] The Sunlight Foundation accused Hastert of failing to disclose that the construction of the highway would benefit a land investment that Hastert and his wife made in nearby land in 2004 and 2005. Hastert took an unusually active role advancing the bill, even though it was opposed by a majority of area residents and by the Illinois Department of Transportation.[96] When he became frustrated by negotiations with White House staff, Hastert began working on the bill directly with President Bush.[96] After passage, Bush traveled to Hastert's district for the law's signing ceremony.[96]

Four months later Hastert sold the land for a 500% profit.[96] Hastert's net worth went from $300,000 to at least $6.2 million.[96] Hastert received five-eighths of the proceeds of the sale of the land, turning a $1.8 million profit in under two years.[94][95][97] Hastert's ownership interest in the tract was not a public record because the land was held by a blind land trust, Little Rock Trust No. 225.[93] There were three partners in the trust: Hastert, Thomas Klatt, and Dallas Ingemunson. However, public documents only named Ingemunson, who was the Kendall County Republican Party chairman and Hastert's personal attorney and longtime friend.[93][97] Hastert denied any wrongdoing.[94] In October 2006, Norman Ornstein and Scott Lilly wrote that the Prairie Parkway affair was "worse than FoleyGate" and called for Hastert's resignation.[96]

In 2012, after Hastert had departed from Congress, the highway project was killed after federal regulators retracted the 2008 approval of an environmental impact statement for the project and agreed to an Illinois Department of Transportation request to redirect the funds for other projects.[98] Environmentalists, who opposed the project, celebrated its cancellation.[98]

In 2006, Hastert (along with then-Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi) criticized an FBI search of Representative William J. Jefferson's Capitol Hill office in connection with a corruption investigation. Hastert issued a lengthy statement saying that the raid violated the separation of powers, and later complained directly to President Bush about the matter.[99][100]

Departure from Congress

[edit]Before the 2006 elections, Hastert expressed his intent to seek reelection as Speaker if the Republicans maintained control of the House. Hastert was reelected for an eleventh term to his seat in the House with nearly 60 percent of the vote, but that year the Republicans lost control of both the Senate and the House to the Democrats following a wave of voter discontent with the Iraq War, the Federal response to Hurricane Katrina, and a series of scandals among congressional Republicans.[101] The day after the November election, Hastert announced he would not seek to become minority leader when the 110th Congress convened in January 2007.[102] Later that month, John Boehner of Ohio defeated Mike Pence of Indiana in a 168–27 vote of the House Republican Conference election to become minority leader for the 110th Congress.[103] The House Democratic Caucus unanimously selected House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi to be Speaker (succeeding Hastert) for the 110th Congress.[103]

In October 2007, following months of rumors that Hastert would not serve out his term, the Capitol Hill newspaper Roll Call reported that Hastert had decided to resign from the House before the end of the year, triggering a special election.[104]

On November 15, 2007, Hastert delivered a farewell speech on the House floor, emphasizing the need for civility in politics; Hastert's speech was followed by remarks from Pelosi praising Hastert's service.[105][106] On November 26, 2007, Hastert submitted his resignation.[107]

Financial disclosure documents indicate that Hastert made a fortune from land deals during his time in Congress.[93] Hastert entered Congress in 1987 with a net worth of no more than $270,000.[17] At the time, his most valuable asset was a 104-acre farm in southern Illinois (which his wife had inherited), worth between $50,000 and $100,000.[93] When Hastert left Congress twenty years later, he reported a significantly increased net worth, variously reported as between $4 million and $17 million[17] and between $3.1 million and $11.3 million.[93] Much of this increase in net worth was the result of various real-estate investments during Hastert's time in Congress (including the controversial land deal several miles from the proposed Prairie Parkway site).[93] At the time Hastert left Congress, much of his net worth remained tied up in real-estate holdings.[17]

State Senator Chris Lauzen, Geneva Mayor Kevin Burns, and wealthy dairy businessman Jim Oberweis all entered the campaign for the Republican nomination to succeed Hastert.[108] In December 2007, Hastert endorsed Oberweis in the primary, and Burns withdrew from the race.[108] In the contentious February 2008 primary election, Oberweis was chosen as the Republican nominee, and Fermilab scientist Bill Foster was selected as the Democratic nominee. In the special election in March 2008 to fill the rest of Hastert's unexpired term, Foster won a surprise victory over Oberweis.[109] In a rematch in the November 2008 elections for a full two-year term, Foster again defeated Oberweis.[110]

Post-congressional career

[edit]Lobbyist and consultant

[edit]In May 2008, six months after resigning from Congress, the Washington, D.C.-based law firm and lobbying firm Dickstein Shapiro announced that Hastert was joining the firm as a senior adviser.[111] Hastert waited until the legally required "cooling-off period" had passed in order to register as a lobbyist.[111] Over the next several years, Hastert earned millions of dollars lobbying his former congressional colleagues on a range of issues, mostly involving congressional appropriations.[112]

According to Foreign Agents Registration Act filings, Hastert represented foreign governments, including the government of Luxembourg and government of Turkey.[111] During parts of 2009, Hastert also lobbied on behalf of Oak Brook, Illinois-based real estate developer CenterPoint Properties, lobbying for the placement of a major Army Reserve transportation facility.[111][112] Hastert also represented Lorillard Tobacco Co., which paid Dickstein Shapiro almost $8 million from 2011 to 2014 to lobby on behalf of candy-flavored tobacco and electronic cigarettes; Hastert "was the most prominent member of the lobbying team" on these efforts.[112] In 2013 and 2014, Hastert lobbied on climate change issues on behalf of Peabody Energy, the world's largest private-sector coal company; in 2015, Hastert "switched sides" and lobbied for Fuels America, the ethanol industry group.[112] In the second half of 2011, Hastert monitored legislation on GPS on behalf of LightSquared, which paid Dickstein Shapiro $200,000 for lobbying services.[112]

Hastert also lobbied on behalf of FirstLine Transportation Security, Inc. (which sought congressional review of Transportation Security Administration procurement);[112] Naperville, Illinois-based lighting technology company PolyBrite International;[111] the American College of Rheumatology (on annual labor and health spending bill);[112] the San Diego, California-based for-profit education company Bridgepoint Education;[111] REX American Resources Corp.;[113] The ServiceMaster Co.;[113] and the Secure ID Coalition.[17]

In 2014, Hastert's firm Dickstein Shapiro and the lobbying firm of former House majority leader-turned lobbyist Dick Gephardt split a $1.4 million annual lobbying contract with the government of Turkey.[114] In April 2013, Hastert and Gephardt traveled with eight members of Congress to Turkey, with all expenses paid by the Turkish government.[114][115] While members of Congress are generally prohibited from corporate-funded travel abroad with lobbyists (a rule enacted after the Jack Abramoff scandal), the law permits lobbyists to plan and attend trips overseas if paid for by foreign countries.[114] Hastert defended the trip, saying that he had "meticulously" followed the rules and that the involvement of himself and Gephardt "allowed those members of Congress who were there to have a fuller experience."[114] A National Journal investigation highlighted the trip as an example of loopholes creating a situation in which "lobbyists who can't legally buy a lawmaker a sandwich can still escort members on trips all around the world."[115]

In March 2015, Hastert along with his associate (accompanied by several lobbyist associates, including former Representative William D. Delahunt of Massachusetts) took advantage of his privilege as a former lawmaker to be present in the Senate Reception Room near the Senate chamber, "lingering" and "bantering with senators and other passersby" during a vote on whether to retain the fuel standard mandating the blending of ethanol and other alternative fuels with gasoline, as advocated by Hastert's client Fuels America (the ethanol industry trade group).[116] Hastert and Delahunt were criticized by watchdog groups who "questioned whether Hastert was violating" these rules,[117] but "allies of Hastert and Delahunt said they made a point of not lobbying lawmakers in the Senate Reception Room, but that they and members of their team used the lobby area as a temporary base, where they could greet lawmakers while they were holding meetings in private rooms."[116]

The day the 2015 indictment was unsealed, Hastert resigned his lobbyist position at Dickstein Shapiro, and his biography was removed from the firm's website.[118][119][120]

In addition to his lobbyist job, Hastert established his own consultancy, Hastert & Associates.[113] In 2008, Hastert also joined the board of directors of Chicago-based futures exchange company CME Group (which had been formed from the merger of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and Chicago Board of Trade), where he earned more than US$205,000 in total compensation in 2014.[121][122] On May 29, 2015, following his indictment, Hastert resigned from the board, effective immediately.[122]

Publicly funded post-speakership office

[edit]A controversy arose in 2009 regarding Hastert's receipt of federal funds while a lobbyist.[123][124] Under a 1975 federal law, Hastert, as a former House Speaker, was entitled to a public allowance (about $40,000 a month) for a five-year period to allow him to maintain an office.[123] Hastert accepted the funds, which went toward office space in far-west suburban Yorkville, Illinois; salaries for three staffers (secretary Lisa Post and administrative assistants Bryan Harbin and Tom Jarman, each paid an annual salary of more than $100,000 over 2½ years); lease payments on a 2008 GMC Yukon sport utility vehicle; a satellite TV subscription; office equipment; and legal fees.[113][123][124] Jarman later left the office, and Harbin's salary was cut substantially.[113] Hastert's government-funded office closed in late 2012, at the end of the maximum five years for which public funds were provided.[113] The total amount of public funds spent on Hastert's post-speakership office was nearly $1.9 million (not including federal benefits such as health care to which the employees were entitled), of which the majority (about $1.45 million) went toward staff salaries.[113]

The federally funded benefits were legally required to be completely separate from Hastert's simultaneous lobbying activities for Dickstein Shapiro.[123][124] The arrangement was criticized as "really concerning" by Steve Ellis, vice president of Taxpayers for Common Sense, because the exact nature of the two roles was not transparent. A Hastert spokesman stated that the two offices were completely separate.[123][124] In 2012, however, a Chicago Tribune investigation found that "a secretary in the ex-speaker's government office used email to coordinate some of his private business meetings and travel, and conducted research on one proposed venture" and that "a suburban Chicago businessman who was involved in the business ventures with Hastert said he met with Hastert at least three times in the government office to discuss the projects."[125] Hastert denied that he had engaged in any improper conduct.[125]

Civil lawsuit alleging personal use of publicly funded office

[edit]In 2013, Hastert's former business partner J. David John filed a lawsuit in the federal district court for the Northern District of Illinois, alleging that Hastert misappropriated federal funds for his post-speakership office in Yorkville for personal use, including private lobbying and business projects.[126][127] This suit was filed under the qui tam provision of the False Claims Act (FCA), an anti-fraud statute that allows a private party to pursue a case on behalf of the federal government.[126][127][128] In the suit, John asserts that he told the FBI in 2011 that "he had knowledge that Hastert was using federally funded offices, staff, office supplies and vehicles for personal business ventures."[126] John, a businessman from the Chicago suburb of Burr Ridge, Illinois,[125][128] also said that he traveled with Hastert and collaborated with him on "a planned Grand Prix racetrack in Southern California and sports events to be organized in the Middle East" as well as other projects.[126] Hastert denies any wrongdoing.[127] The allegations about the use of the former speakers' officer first drew the attention of federal investigators in 2013, leading to the federal indictment in 2015.[129]

In April 2017, Kocoras dismissed the suit, finding that John did not qualify as a "whistleblower" under the FCA.[130] John's attorney said that an appeal was possible.[130] The dismissal "did not turn on whether Hastert actually misused the speaker's office, but rather whether John met a prerequisite for [a False Claims Act] suit: that he brought the allegations to the government's attention before anyone else and before they were made public."[131] Kocoras held that John had falsely claimed that he had told the FBI about possible misuse of federal resources by Hastert.[131]

Other activities

[edit]After retiring from Congress, Hastert made occasional public appearances on political programs.[66] He also made some endorsements of political candidates; in the 2012 Republican presidential primaries, he endorsed Mitt Romney instead of his predecessor as Speaker, Newt Gingrich.[132]

Sex abuse scandal and federal prosecution

[edit]Investigation into hush-money scheme

[edit]According to a 2017 interview with the two special agents leading the investigations—one each from the FBI and the IRS Criminal Investigation Division—"Hastert had been on the FBI's radar as early as November 2012—even before the FBI and IRS began investigating the suspicious cash withdrawals that were Hastert's downfall."[129] The inquiry was first prompted by allegations that Hastert had used his taxpayer-funded Office of the Former Speaker to further his private business ventures, something that Hastert was never charged with.[129] In 2013, the FBI and IRS began investigating Hastert's cash withdrawals, and in early 2015 they had learned about the "hush money" agreement between "Individual A" and Hastert.[129] In a December 8, 2014, interview, Hastert lied to the federal agents about the purpose of the withdrawals, leading to his federal prosecution.[129]

Indictment

[edit]On May 28, 2015, a seven-page indictment of Hastert by a federal grand jury was unsealed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois in Chicago.[133][134][135][136]

The indictment charged Hastert with unlawfully structuring the withdrawal of $952,000 in cash in order to evade the requirement that banks report cash transactions over US$10,000 (Title 31, United States Code, Section 5324(a)(3)), and making false statements to the FBI about the purpose of his withdrawals (Title 18, United States Code, Section 1001(a)(2)). The indictment alleges that Hastert agreed to make payments of $3.5 million to an unnamed subject (identified in the indictment only as an "Individual A" from Yorkville, Illinois, who was known to Hastert for "most of Individual A's life"). The indictment stated that the payments were to "compensate for and conceal [Hastert's] prior misconduct."[66][137][138][134][135][139] Federal authorities began investigating his withdrawals in 2013.[140] In late 2014, after being questioned about the withdrawals, Hastert said that he did not trust banks; shortly afterward, Hastert changed his story, saying that he "was the victim of extortion by Individual A for false molestation accusations."[7]

The indictment itself did not specify the exact nature of the "past misconduct" referred to.[17] The U.S. Attorney's Office limited details in the indictment of Hastert, in part because of a request from Hastert's attorneys.[141][142][143]

On May 29, Hastert was released on his own recognizance on a preliminary bail of $4,500 set by a magistrate judge.[122][142]

In June The New York Times reported that Hastert had approached a business associate, J. David John, in 2010, to look for a financial adviser to come up with an annuity plan that would "generate a substantial cash payout each year."[144] This request was the same year that prosecutors say he agreed to start paying hush money to the person he allegedly committed misconduct against.[145] John told the Times that "I did not think much about it at the time, but looking back at it, it does seem strange. He just said he needed to generate some cash."[144]

Sex abuse allegations emerge

[edit]On May 29, 2015, after Hastert had been indicted for illicitly structuring financial transactions, two people briefed on the evidence from the case stated that "Individual A"—the man to whom Hastert was making payments—had been sexually abused by Hastert during Hastert's time as a teacher and coach at Yorkville High School and that Hastert had paid $1.7 million out of a total $3.5 million in promised payment.[21] On the same day, the Los Angeles Times reported that investigators had spoken with another former student who made similar allegations that corroborated what the first student said.[146] Hastert admitted to committing sexual abuse during sentencing on the structuring charge.[7][147]

On June 5, 2015, ABC News' Good Morning America aired an interview with Jolene Reinboldt Burdge, the sister of Steve Reinboldt, who was the student equipment manager of the wrestling team at Yorkville High School when Hastert was the wrestling coach.[148][149][150] Hastert also ran an Explorers group of which Steve Reinboldt was a member and led the group on a diving trip to the Bahamas.[148] In the interview, Burdge stated that in 1979, eight years after Reinboldt's high school graduation in 1971, her brother had told her that he had been sexually abused by Hastert throughout his four years of high school.[148] Burdge said that she was "stunned" by this news and that her brother said that he had never told anyone before, because he did not think he would be believed.[148] A message from Hastert appears in Steve Reinboldt's 1970 high school yearbook.[148] In the interview, Burdge said that she believes the abuse stopped when her brother moved away after graduation. Jolene said that Hastert "damaged Steve I think more than any of us will ever know".[148]

Reinboldt died of an AIDS-related illness in 1995.[148] Hastert attended his viewing, which angered Burdge. She said:

I was just there just trying to bite my tongue thinking that blood was coming out because I was just ... So after he had gone through the line I followed him out into the parking lot of the funeral home. I said, "I want to know why you did what you did to my brother." And he just stood there and stared at me. He didn't say, "What are you talking about?" you know, [or], "What? I don't know what you're talking about." He just stood there and stared at me. Then I just continued to say, "I want you to know your secret didn't die in there with my brother. And I want you to remember that I'm out here and that I know." And again, he just stood there and he did not say a word.[148]

Hastert then got in his car and left. Burdge said Hastert's lack of a response "said everything".[148]

Following Reinboldt's death, around the time that the Mark Foley scandal broke in 2006, Burdge unsuccessfully attempted to bring the allegations against Hastert to light. She contacted ABC News and the Associated Press (AP) on an off-the-record basis, and also contacted some advocacy groups.[148][149] ABC News and the AP could not corroborate Burdge's allegation at the time, and Hastert denied the accusation to ABC News at the time, so the claim was not published.[148][149][151]

ABC News reported that "for years, Jolene watched helplessly as Hastert basked in fame and power, seated to the left of the president for years in the early 2000s, during the nationally televised State of the Union address".[148] Several days before the indictment was unsealed, Burdge was interviewed by FBI agents who asked her about her brother and informed her Hastert was about to be indicted on federal charges.[148] Neither Reinboldt nor Burdge are "Individual A" named in the indictment, but Burdge believes that "Individual A" is familiar with what happened with her brother.[148] The statements by Burdge "marked the first time that a person [had] been publicly identified as a possible victim of Mr. Hastert".[152]

Reactions

[edit]The emergence of the sexual abuse allegations against Hastert brought renewed attention to the 2006 Mark Foley scandal, and the criticism of Hastert that he failed to take appropriate action in that case.[153][154]

In the wake of the sexual abuse allegations, journalists noted that Hastert was a supporter of measures which sought to enhance punishments for child sexual abuse, such as the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act and the Child Abuse Prevention and Enforcement Act of 2000.[155][156] In 2003, Hastert publicly called for legislation to "put repeat child molesters into jail for the rest of their lives".[156]

Hastert resigned his lobbyist position at the law and lobbying firm Dickstein Shapiro the day the indictment was unsealed.[118][119][120] His biography was quickly removed from the firm's website and the firm purged all mentions of him from its previously posted press releases.[117] According to a report in Politico, Hastert's resignation left the firm "reeling".[117] Following the Hastert indictment, Dickstein Shapiro's biggest domestic client, Fuels America, terminated its lobbying contract with the firm.[117]

On May 29, 2015, Yorkville Community Unit School District 115 released a statement reading:

The District was first made aware of any concerns regarding Mr. Hastert when the federal indictment was released on May 28, 2015. Yorkville Community Unit School District #115 has no knowledge of Mr. Hastert's alleged misconduct, nor has any individual contacted the District to report any such misconduct. If requested to do so, the District plans to cooperate fully with the U.S. Attorney's investigation into this matter.[157]

James Harnett, who was superintendent of the school district for five of the years that Hastert taught there, told the Chicago Tribune that he was not aware of any complaints of misconduct brought against Hastert at the time.[20]

On May 29, 2015, Senator Mark Kirk, Republican of Illinois, who served in the House throughout Hastert's tenure as speaker, released a statement reading: "Anyone who knows Denny is shocked and confused by the recent news. The former speaker should be afforded, like any other American, his day in court to address these very serious accusations. This is a very troubling development that we must learn more about, but I am thinking of his family during this difficult time."[20] On June 4, 2015, Kirk announced that he would donate to charity a $10,000 contribution made to Kirk's 2010 Senate campaign by Hastert's Keep Our Mission PAC.[158] Kirk's announcement was made following the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC)'s call upon the senator to "return or donate Denny Hastert's money immediately".[159] The DSCC also called upon Republican Senators John Boozman of Arkansas and Roy Blunt of Missouri (who received $11,000 and $5,000, respectively, from Hastert's PAC in recent years) to return or donate the funds.[158]

On May 29, 2015, White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest stated in response to a reporter's question that "there is nobody here" at the White House "who derives any pleasure from reading about the former Speaker's legal troubles at this point".[160][161] On the same day, House Speaker John Boehner, Republican of Ohio, issued a statement saying: "The Denny I served with worked hard on behalf of his constituents and the country. I'm shocked and saddened to learn of these reports."[21][162]

On May 30, 2015, Illinois's other senator, Dick Durbin, a Democrat, stated:

It seems so out of character for Denny. I just never could imagine that he'd be involved in anything like this ... We had our political differences, as you might expect, but I respected him as a colleague in the Illinois delegation and as Speaker.[163]

On June 2, 2015, former Federal Housing Finance Agency director and former U.S. Representative Mel Watt, Democrat of North Carolina, released a statement saying:

Over 15 years ago I heard an unseemly rumor from someone who, contrary to what has been reported, was not an intermediary or advocate for the alleged victim's family. It would not be the first nor last time that I, as a Member of Congress, would hear rumors or innuendoes about colleagues. I had no direct knowledge of any abuse by former Speaker Hastert and, therefore, took no action.[164]

The Hastert scandal was named by MSNBC as among the "top political sex scandals of 2015,"[165] by the Associated Press as one of the "top 10 Illinois stories of 2015,"[166] and by ABC News as one of the "biggest moments on Capitol Hill in 2015."[167] Hastert's sentencing was also named by the Associated Press as one of "top 10 Illinois stories of 2016".[168]

Arraignment and pretrial proceedings

[edit]The case was assigned to U.S. District Judge Thomas M. Durkin.[17] In between the unsealing of the indictment and the arraignment, Hastert made no public appearances and did not release any public statement.[169][170] However, on May 29, 2015, CBS Chicago reported that Hastert had privately told close friends that "I am a victim, too" and that he was sorry they had to go through the ordeal.[171]

Hastert hired attorney Thomas C. Green, a white-collar criminal defense lawyer and senior counsel at the Washington, D.C. office of the law firm Sidley Austin, to defend him.[137][172] The prosecutors assigned to the case were originally Assistant United States Attorneys Steven Block and Carrie Hamilton.[173] Hamilton left the U.S. Attorney's Office in July 2015 after being appointed as a judge of the Circuit Court of Cook County; Diane MacArthur replaced Hamilton on the Hastert prosecution team.[173]

The June 9, 2015, arraignment generated a degree of media interest at the Everett McKinley Dirksen United States Courthouse not seen since the proceedings against Illinois governors Rod Blagojevich and George Ryan on corruption charges.[174][175] The Chicago Tribune reported: "Hastert's entrance and exit from the courthouse touched off a wild scene as federal Homeland Security agents escorted Hastert and his attorneys to and from a waiting vehicle amid a crush of television news crews and photographers."[176] At the hearing, Hastert entered a plea of not guilty.[137][138][177] Durkin set a $4,500 unsecured bond as well as various other conditions of pretrial release, and Hastert surrendered his passport.[178]

At the arraignment, Durkin disclosed that he had contributed $500 in 2002 and $1000 in 2004 to the Hastert for Congress campaign; the contributions were made while Durkin was a partner at the law firm Mayer Brown, before he was appointed to the federal bench in 2012.[179] Hastert's son, Ethan, was a partner at Mayer Brown.[179] At the arraignment, Durkin stated that he had never met Hastert and that he believed he could be impartial, but gave the parties time to decide whether to object to his involvement in the case.[177][178][180] On June 11, federal prosecutors and Hastert's lawyers filed notices waiving any objection to Durkin presiding over the case.[181][182]

On June 12, federal prosecutors, with the agreement of Hastert's attorneys, filed a motion for a protective order seeking to bar the public disclosure of the identity of "Individual A" and other sensitive information.[183] The motion states that "the discovery to be provided by the government in this case includes sensitive information, the unrestricted dissemination of which could adversely affect law enforcement interests and the privacy interests of third parties."[183] The draft order contained language directing the parties to file any such sensitive information under seal.[183] On June 16, Durkin granted the motion for a protective order[184][185] but did not sign such an order.[186]

At a status hearing on July 14 (which Hastert again did not attend), the parties updated the court on preparations for trial.[187] At the hearing, Green said: "The indictment has effectively been amended by leaks from the government. It is now an 800-pound gorilla in this case. It has been injected in this case I think impermissibly. (The question is) whether I wrestle with that gorilla or I don't wrestle with that gorilla."[188] Green also said that the defense would file a motion to dismiss the indictment, possibly under seal.[188] Durkin "cautioned that even if he allows part or all of the motion to be hidden from the public, his ruling would be public and likely would disclose sealed portions of the motion."[188] At the same hearing, the prosecution said that they expected a trial to last about two weeks.[188]

Hastert shut down his "Keep Our Mission" leadership PAC at the end of June 2015 and transferred $10,000 (the vast majority of the PAC's remaining funds) to a new legal defense fund, the J. Dennis Hastert Defense Trust.[189][190] A Federal Elections Commission report lists the defense fund's address as a Sunapee, New Hampshire property owned by Republican donor and ex-Gerald Ford White House staffer James Rooney.[189]

Guilty plea

[edit]On September 11, 2015, Durkin granted a joint motion by the government and by Hastert to extend the deadline for filing pretrial motions for two weeks, "giving the two sides more time for discussions they have been engaged in."[191] On September 22, the parties filed another joint motion requesting another two-week extension (from September 28 to October 13); the motion said that the parties were discussing issues that Hastert "may raise in pretrial motions" but provided no details.[192] At a hearing on September 28, Hastert's attorneys and the government confirmed that they were discussing a possible plea agreement. Judge Durkin said that if no plea agreement was reached, he wanted the case to go to trial in March or April 2016.[193] Pretrial motions were due on October 13, but none were filed, indicating that Hastert and the government "were nearing a plea deal."[136]

On October 15, 2015, it was announced at a court hearing that Hastert and federal prosecutors had reached a plea agreement.[136] On October 28, 2015, under the plea agreement, Hastert appeared in court (the only time Hastert appeared personally in court after the arraignment) and pleaded guilty to the felony structuring charge.[5][194] The charge of "making false statements" (lying to the FBI) was dismissed.[195]

Hastert said in court: "I didn't want them [bank officials] to know how I intended to spend the money. I withdrew the money in less than $10,000 increments."[194] Possible sentences within a preliminary Federal Sentencing Guidelines calculation ranged from probation to six months in prison.[5][196][197]

The plea agreement allowed Hastert "to avoid a potentially long and embarrassing trial" and was thought to enable him to "keep secret information that he has hidden for years."[5][136][194]

Sentencing and admission of past sex abuse

[edit]Soon after pleading guilty, Hastert suffered a stroke, and was hospitalized from November 2015 to January 15, 2016.[197] Hastert remained free on bail pending sentencing.[195]

Sentencing was originally set for February 29, 2016.[194] However, in late January 2016, Hastert's attorneys asked the court to delay sentencing due to Hastert's ongoing health problems,[197] and Judge Durkin postponed sentencing until April 8, 2016.[198] In March, Durkin ordered the appointment of a medical expert to review Hastert's health in preparation for sentencing.[199] Later in March, Durkin postponed the sentencing hearing (over the objection of Hastert's attorneys) to April 27 so that a man who alleged sexual abuse by Hastert (identified as "Individual D" in court) could testify at the sentencing.[200]

In early April, the parties filed submissions in court ahead of sentencing.[2] The maximum sentence for the offense was five years in prison and a $250,000 fine,[119] although the Federal Sentencing Guidelines range was from probation to six months.[5][196] Hastert asked for probation.[7][2] A statement released by Hastert's counsel said: "Mr. Hastert acknowledges that as a young man, he committed transgressions for which he is profoundly sorry. He earnestly apologizes to his former students, family, friends, previous constituents and all others affected by the harm his actions have caused."[2][201] Hastert did not provide details.[2][201]

Hastert also filed under seal a response to the government's presentence investigation report.[2] In the prosecution's filing ahead of sentencing, federal prosecutors made allegations of sexual misconduct against Hastert (the first time they had done so publicly), saying that he had molested at least four boys as young as 14 (including Steve Reinboldt and others) while he worked as a high school wrestling coach decades earlier.[2] In a 26-page filing, prosecutors detailed "specific, graphic incidents" of sexual acts.[2][202] Prosecutors asked for a six-month sentence, as called for under federal sentencing guidelines.[2] Prosecutors also requested the court to order Hastert to undergo a sex offender evaluation and comply with any recommended treatment.[2] While Hastert's health problems had the possibility to help him avoid prison,[203] prosecutors noted in their court filing that he could receive medical treatment while incarcerated, if necessary.[2]

Sixty letters asking for leniency for Hastert were submitted to the court ahead of sentencing, but 19 of these letters were withdrawn after Judge Durkin said that he would not consider any letters that were not made public.[204] Of the 41 letters that were made public, several were from current or former members of Congress: Tom DeLay, John T. Doolittle, David Dreier, Thomas W. Ewing, and Porter Goss (who also is a former CIA director).[205] The Chicago Tribune noted that DeLay and Doolittle "have had legal troubles of their own" stemming from the Abramoff scandal, although DeLay's conviction in that scandal was later overturned and Doolittle was never charged.[204] Other supporters of Hastert who wrote letters on his behalf included his family members; former Illinois Attorney General Tyrone C. Fahner; "local leaders, board members, police officers and others from his home base in rural Kendall County"; and "several members of Illinois' wrestling community."[204]

At the sentencing hearing on April 27, 2016, the government presented two witnesses. Jolene Burdge, the sister of Steve Reinboldt, read a letter that her brother had written shortly before his death in 1995. Addressing Hastert, Burdge stated that she wanted to "hold you accountable for sexually abusing my brother. I knew your secret, and you couldn't bribe or intimidate your way out. ... You think you can deny your abuse of Steve because he can no longer speak for himself – that's why I'm here."[6]

The second witness was Scott Cross ("Individual D") who publicly identified himself for the first time. Cross gave emotional testimony, telling the court that Hastert, whom he had trusted, had abused him and caused him to experience "intense pain, shame and guilt."[7][6][206] Cross' oldest brother is longtime Illinois House of Representatives Republican leader Tom Cross, a political protégé of Hastert's.[6][206]

Addressing the court, Hastert—who had arrived at court in a wheelchair—read from a written statement, apologizing for having "mistreated athletes."[6] After being pressed by the judge, Hastert admitted to sexually abusing boys whom he coached, saying that he had molested "Individual B" and did not remember some of the others.[6] Hastert said he did not remember abusing Cross, "but I accept his statement."[6] Hastert stated "what I did was wrong and I regret it ... I took advantage of them."[6] Hastert also acknowledged that he had misled the FBI.[6] Durkin referred to Hastert as a "serial child molester" and imposed a sentence of 15 months in prison, two years' supervised release, including sex-offender treatment, and a $250,000 fine.[7][3] Hastert is "one of the highest-ranking American politicians ever sentenced to prison."[3]

Hastert could not be prosecuted for any of the acts of sexual abuse of which he had been accused because the applicable statute of limitations had expired decades earlier.[207]

Reactions

[edit]Following the sentence, the Chicago Tribune editorial board praised "the bravery of the victims and their families who confronted the man who was once second in line to be president" and wrote of the sentence: "The enduring impact is that the truth has been revealed. And for as long as the name Dennis Hastert is recalled, the man once respected as a leader will be known as a criminal, a scoundrel, a child molester."[208] The Washington Post editorial board hailed the sentence, writing that Hastert's victims "should not have had to struggle with what Mr. Hastert did to them all the while they watched him rise in stature and power."[209] The Post called for extending statutes of limitations in sex abuse cases to give victims more time to come forward and prosecutors more time to pursue perpetrators.[209] New York Times columnist Frank Bruni wrote that Hastert's case underscored the danger that comes with the "quickness and frequency with which so many of us equate displays of religious devotion with actual rectitude," noting that Hastert's public displays of Christian faith during his time in office were "a factor in his colleagues' assessments of him as safe, uncontroversial."[210] Bruni also critiqued the testimonials that prominent Republicans submitted on Hastert's behalf before sentencing, saying that these "affirm the degree to which pacts rather than principle govern partisan politics today."[210]

Jacob Sullum of Reason opined that the financial structuring offense to which Hastert pleaded guilty "should not be a crime ... even if it occasionally provides the means for punishing actual criminals who would otherwise escape justice."[211] Conor Friedersdorf of The Atlantic expressed similar views, writing: "The alarming aspect of this case is the fact that an American is ultimately being prosecuted for the crime of evading federal government surveillance."[212]

The Hastert scandal was one motivation for the advance of legislation in the Illinois General Assembly to eliminate the statute of limitations for all felony child abuse and sexual assault offenses.[213] The measure unanimously passed the state Senate in March 2017.[214]

Incarceration

[edit]Hastert did not appeal his sentence.[215] Shortly after being sentenced, Hastert paid the $250,000 fine[216] and was ordered to report to prison on June 22, 2016.[217] On that date, Hastert reported to the Federal Medical Center in Rochester, Minnesota to begin his prison term.[218]

In July 2017, after serving about 13 months of a 15-month sentence, Hastert was released from federal prison and returned to Chicago under "residential re-entry management" supervision.[8][219]

Abuse-related civil lawsuits

[edit]"James Doe" lawsuit

[edit]In April 2016, "Individual A" sued Hastert for breach of contract in Illinois state court, in Kendall County. "Individual A" (suing under pseudonym "James Doe") sought to collect the remaining $1.8 million in "hush money" allegedly promised to him by Hastert.[220][221][222] In the complaint, "Individual A" alleged that he was molested at age 14 by Hastert and that he confronted Hastert after speaking with another of Hastert's alleged victims in 2008.[220] Individual A alleged that he suffered panic attacks and other problems for years as a result of the abuse.[220] Hastert counterclaimed for return of the hush money, alleging that "Individual A" violated a verbal agreement with him by disclosing the sexual abuse to federal authorities.[221][223]

In November 2016, the court denied Hastert's motion to dismiss.[224] In September 2019, the court denied motions for summary judgment by each side.[225] In September 2021, days before trial was set to begin, Hastert reached a settlement with the plaintiff for an undisclosed amount.[222]

"Richard Doe" lawsuit

[edit]In May 2016, a second man filed a lawsuit against Hastert. The man alleged that Hastert sexually assaulted him in the bathroom of a community building in Yorkville in the summer of either 1973 or 1974, when the man was nine or ten years old and in the fourth grade. The complaint detailed the alleged violent assault as well as threats allegedly made by Hastert. The man only recognized Hastert as the assailant after Hastert appeared at Yorkville Grade School in gym class.[226][227] A Kendall County judge granted the man's motion to proceed anonymously under the "Richard Doe" pseudonym.[226] In the complaint, the man stated that when he was 20 or 21 years old, he comprehended what had occurred and reported the crime to the Kendall County State's Attorney's Office, but that then-state's attorney Dallas C. Ingemunson "threatened to charge him with a crime and accused him of slandering Hastert's name."[226] Ingemunson denied this allegation, calling it "bogus."[226] In May 2016, "Richard Doe" filed a report with the Kendall County Sheriff's Office, but the state's attorney's office determined that the statute of limitations barred a complaint against anyone."[226] NBC Chicago obtained a redacted version of the Sheriff's Office police report.[227]

In November 2017, this lawsuit was dismissed due to the expiration of the statute of limitations years earlier.[228][229]

Impact upon pensions

[edit]Soon after sentencing, the Illinois Teachers' Retirement System announced that Hastert would forfeit future teachers' pension benefits, effective immediately.[230] Hastert challenged this decision on the ground that the specific federal crime to which he pleaded guilty was not directly related to his time as a teacher.[231]

Hastert's pension for his service in the Illinois General Assembly—about $28,000 a year[231]—was originally unaffected.[230] However, in October 2016, the General Assembly Retirement System board of trustees unanimously voted to suspend Hastert's pension[231] and in April 2017 the board voted, 5–2, to terminate the pension.[232]

As of 2015, Hastert continued to receive his congressional pension,[233] which amounts to approximately $73,000 a year.[231]

Honors

[edit]

In December 1999, Northern Illinois University conferred an honorary LL.D. degree upon Hastert.[235] In May 2016, NIU's board of trustees unanimously voted to revoke Hastert's honorary degree.[236]

In 2002, Lewis University conferred an honorary degree upon Hastert. In 2015, following his guilty plea, the university said that it was "reviewing the status of the honorary degree."[237] Lewis University no longer shows Hastert as having earned an honorary degree.

The National Wrestling Hall of Fame awarded Hastert its Order of Merit in 1995 and named Hastert to its "Hall of Outstanding Americans" in 2000.[238][239][240] In May 2016, a few days after Hastert was sentenced to prison, the Hall of Fame (following a review)[238] revoked all of Hastert's honors, the first time the organization had ever taken such an action.[241]

The Three Fires Council of the Boy Scouts of America has honored Hastert with its distinguished service award.[20][239]

In March 2001, President Valdas Adamkus of Lithuania presented Hastert with the Grand Cross of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas.[15][242] In 2004, Hastert was presented the Order of the Oak Crown, Grand Cross by the grand duke of Luxembourg.[15]

In 2007, the J. Dennis Hastert Center for Economics, Government and Public Policy was founded at Wheaton College, the former Speaker's alma mater.[243] Hastert resigned from the board of advisers of the center on May 29, 2015, after the indictment against him was released.[244] On May 31, 2015, the college announced that it was removing his name from the center, renaming it the Wheaton College Center for Economics, Government, and Public Policy.[245]

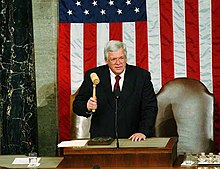

In 2009, Hastert's official portrait was unveiled and placed in the Speaker's Lobby adjacent to the House chamber, alongside portraits of other past House speakers. The 5' by 3½' portrait, executed by Westchester County, New York artist Laurel Stern Boeck, cost $35,000 in taxpayer funds.[234][239] In November 2015, the week after Hastert's guilty plea in his criminal case, the portrait was removed from the Speaker's Lobby on orders of Speaker Paul Ryan.[246]

In May 2009, Hastert accepted the Grand Cross of the Order of San Carlos from Álvaro Uribe, the president of Colombia.[15][247]

In May 2010, Hastert accepted the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun from Akihito, emperor of Japan.[9][248]

In 2012, a plaque funded by private donors, "bearing Hastert's likeness and a list of his accomplishments," was placed in the historic Kendall County Courthouse in downtown Yorkville.[239] The plaque was taken down in 2015, following Hastert's guilty plea.[249]

In early May 2015 (before the indictment was released), a proposal in the Illinois Legislature to spend $500,000 to commission and install a statue of Hastert in the Illinois State Capitol was withdrawn at Hastert's request. Hastert called the measure's sponsor (Michael Madigan, the speaker of the Illinois House of Representatives) and stated that "he appreciated the recognition and honor" but asked that it be deferred given the "fiscal condition" of the state.[250][251]

In 2015, following the unsealing of the indictment against Hastert the previous month, the Denny Hastert Yorkville Invitational, a popular wrestling tournament in Illinois,[252] was renamed the Fighting Foxes Invitational.[253]

Personal life

[edit]Marriage and family

[edit]Hastert has been married to Jean Hastert (née Kahl) since 1973.[9] They have two children, Ethan and Joshua.[9] Hastert's older son, Joshua, was a lobbyist for the firm PodestaMattoon,[254] representing clients ranging from Amgen, a biotech company, to Lockheed Martin, a defense contractor. This provoked criticism from Congress Watch: "There definitely should be restrictions [on family members registering as lobbyists] ... This is family members cashing in on connections ... [and it] is an ideal opportunity for special interest groups to exploit family relationships for personal gain." Joshua Hastert responded to the allegation by saying that he did not lobby House Republican leaders.[255]